A friend wondered if I could do a portrait of her dog. I wondered too, but it sounded like an interesting project. I didn’t realise that pet portraits were a thing until I went online and saw page after page of search results for pet portrait artists.

I’ve never met Cooper, a boxer mastiff cross. Everything was based on a collection of photos taken at different angles, including profile shots and various poses, that let me get some idea of the basic shape of his head.

Working in charcoal seemed the most flexible and natural method for me at the moment, but I really wanted to do an oil painting, just to see what I would come up with. I ended up doing two pieces, one in charcoal of Cooper as he is now (which didn’t quite work—I need to make another attempt), and this oil painting of him as a puppy.

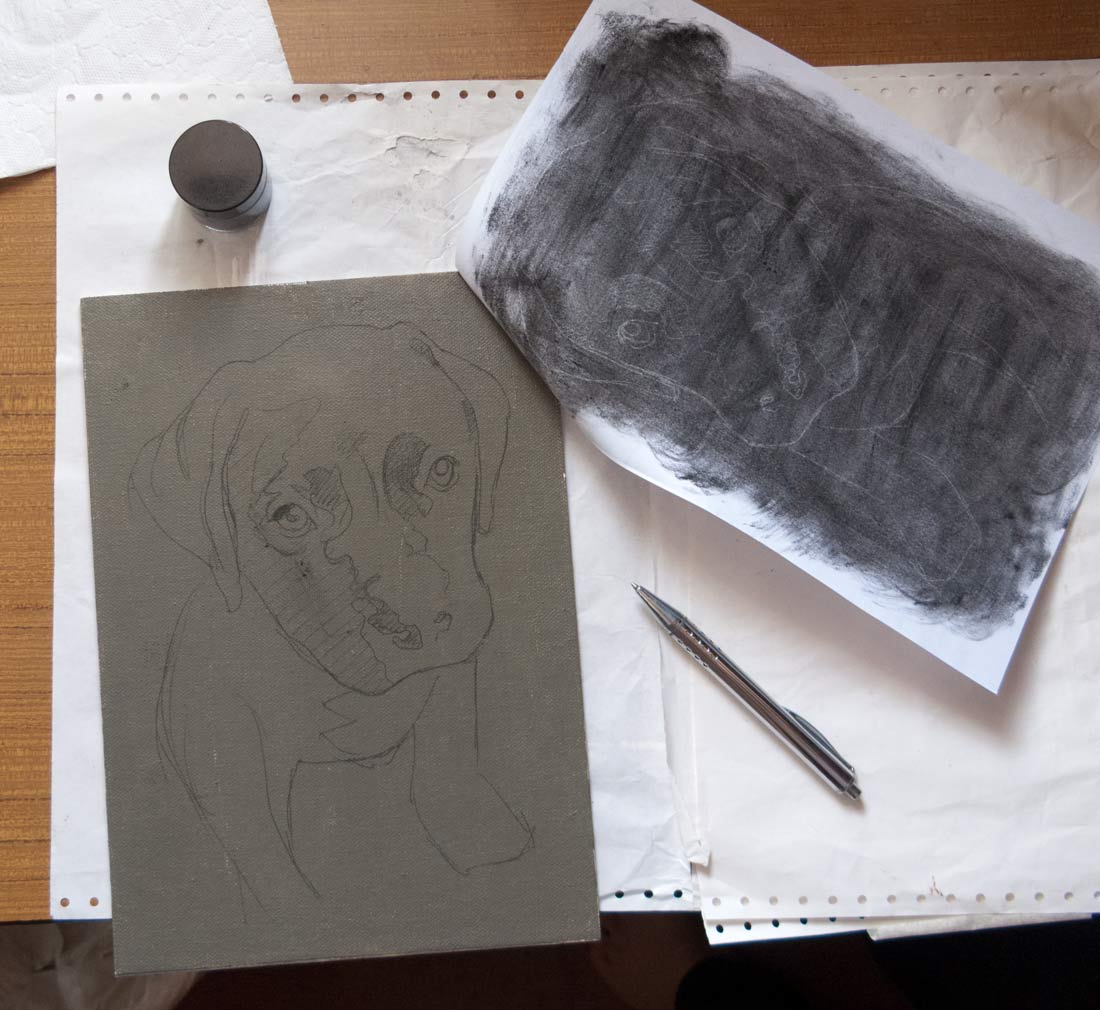

For the puppy painting, I started with some warm-up charcoal and pencil drawings, then used a Polychromos pencil to do a more detailed sketch. I like the Polchromos pencils as they build up gently into darker tones, even though they don’t erase as easily as charcoal.

The pencil sketch was scanned and copied on to office paper and the back covered with old charcoal dust that I keep in a jar. The outlines and tones were transferred onto an A4 canvas mounted on aluminium composite by drawing over the sketch with a ballpoint pen.

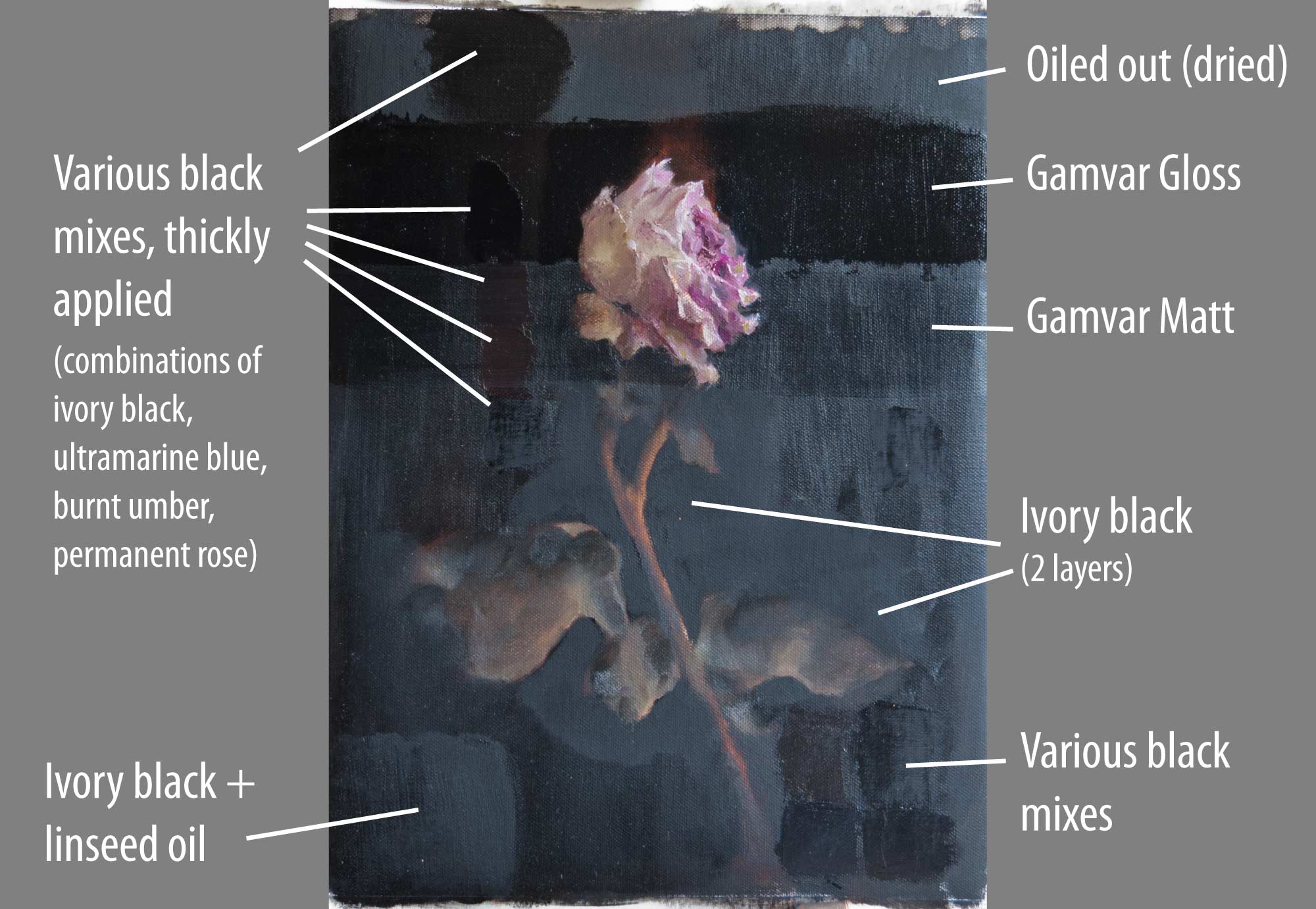

The canvas ground was acrylic gesso covered with a layer of grey mud oil paint left over from a previous painting. Acrylic gesso can be very absorbant and suck the oil out of the upper layers, but this mud preparation acts as a barrier to the thirsty gesso and effectively creates an oil ground that is very pleasant to paint on.

I did about three passes on separate days to build up the painting, with a final pass to make some corrections to the background. I let the painting become touch dry before the next painting session.

I used ivory black in this painting and it’s not a pigment that I’m used to. I bought a tube to mix with titanium white and burnt umber to make neutral greys for reducing the chroma of colour mixes (following Paul Foxton’s method), but it was tempting to use this black instead of my usual mix of ultramarine blue and burnt umber for some of the darkest areas. A problem I’ve found with ivory black is that it sinks in really noticeably. It looks like a deep, silky black when wet but dries a lighter matt, almost like gouache. I don’t know if the oil is sinking in to lower layers or if the pigment itself is soaking up all the oil.

I oiled out the painting at the beginning of each pass, but eventually that thin linseed oil layer also sinks in. I was betting everything on a final varnish using Gamvar Gloss to even things out, which it seems to have done.

He looks cute in this picture. He’s grown up to be the size of a small horse.