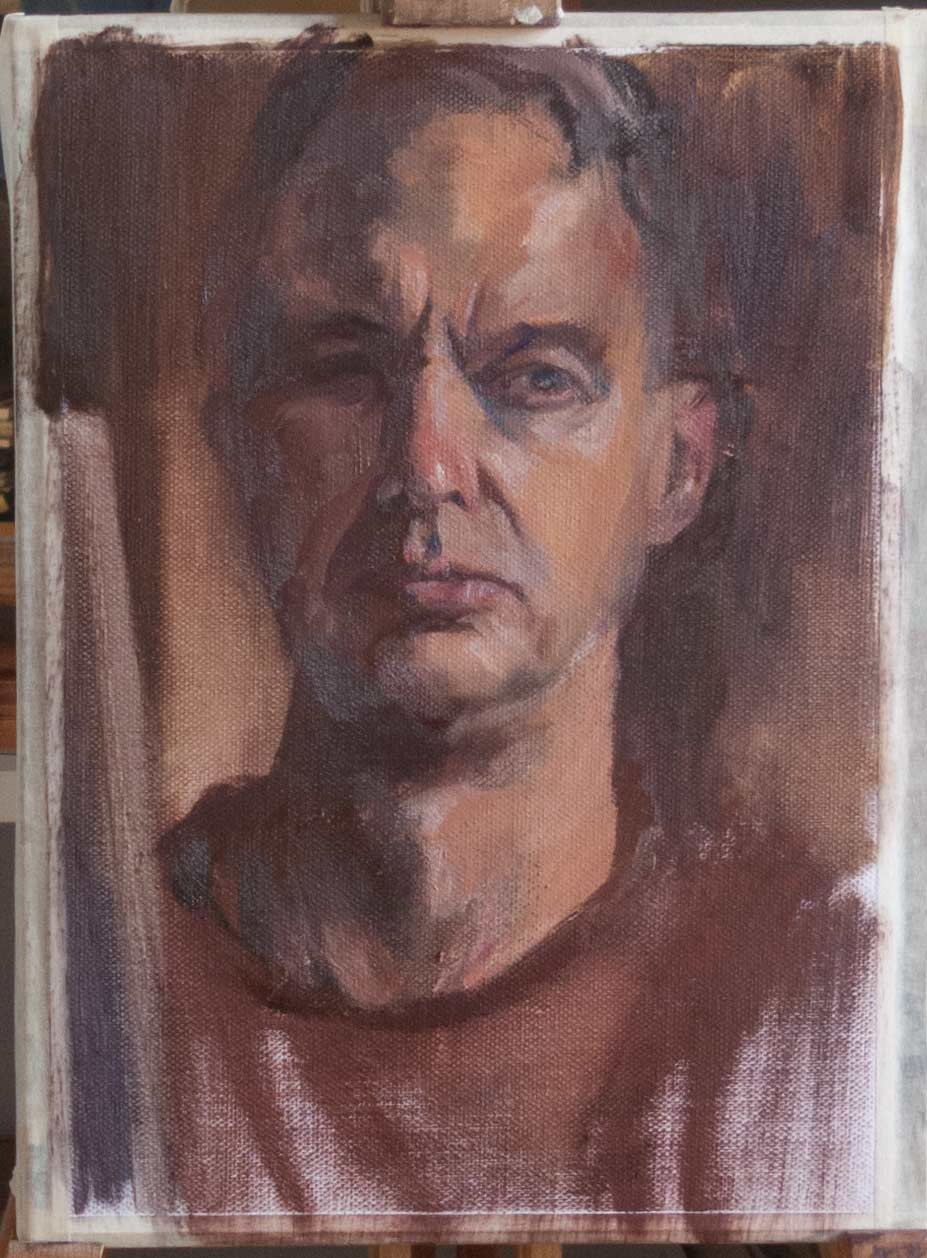

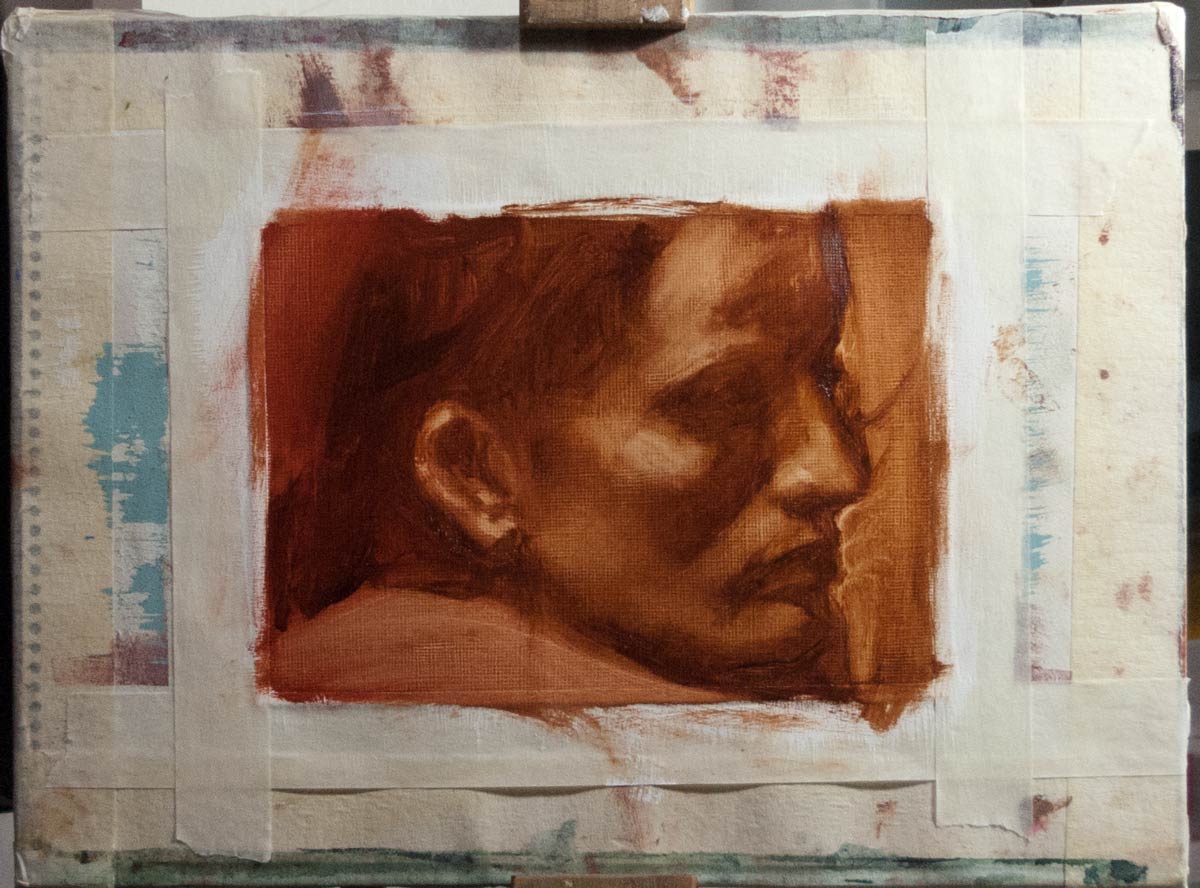

An oil painting of a pencil copy of a drawing found in Risunok: Osnovy uchebnogo akademicheskogo risunka (Figure: Basic educational academic drawing) — a book full of beautiful drawings but with Russian text. I can’t read the words, but at least I can learn something from copying the drawings.

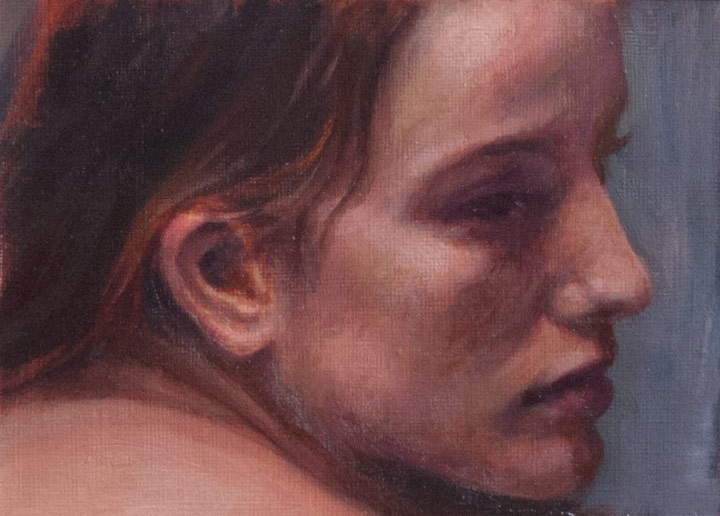

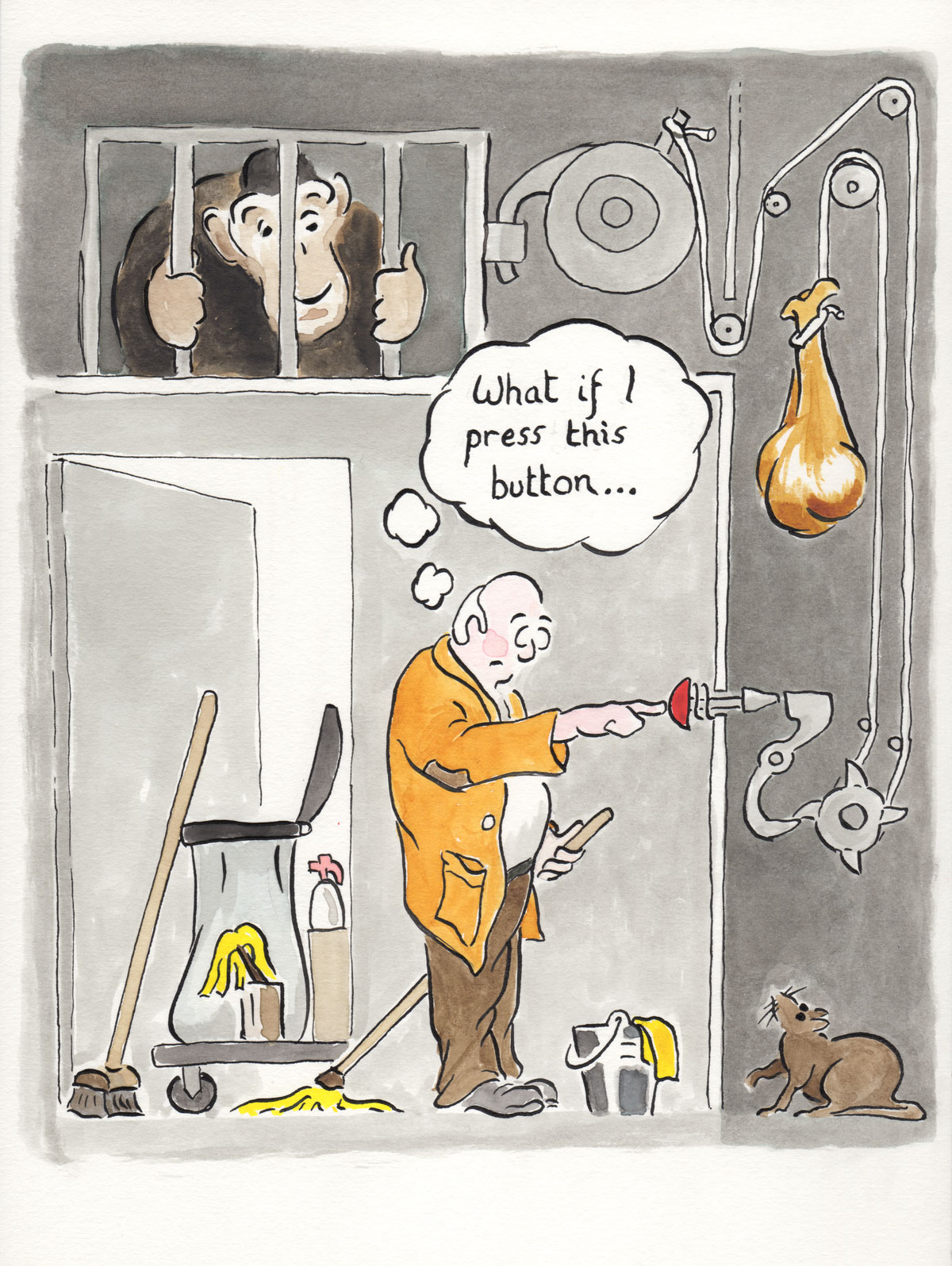

I’m trying to develop the ability to see things in terms of their three-dimensional form, as an object in space, as recommended by Robert Beverley Hale in Drawing Lessons from the Great Masters. He suggests visualising forms in terms of very simple mass:

…the block, the cylinder, the sphere; occasionally the cone; as well as simple combinations and modifications of these forms, principally the egg.

When we wish to create the illusion of reality on the surface of a piece of paper or canvas, nothing is more helpful than the ability to visualise in terms of simple mass. Troublesome problems connected with general shape, proportion, direction, planes, detail, light and shade, and line can all be solved by thinking in terms of simple geometrical masses.

In this painting, many liberties were taken with the lighting, which was developed and invented from the original line drawing. For instance, the light catching the muscle in the top left coming from the shoulder blade is lit too strongly, but I liked it as a centre of interest. I took a picture of the half-finished painting into Photoshop to experiment with the background glow and highlights, and then used that mock-up as a guide for finishing the painting. And the anatomy has no doubt become distorted through the multiple copies (final year students of Medicine & Surgery take note). I recommend Proko.com as a great site to learn how to visualise and draw anatomy.

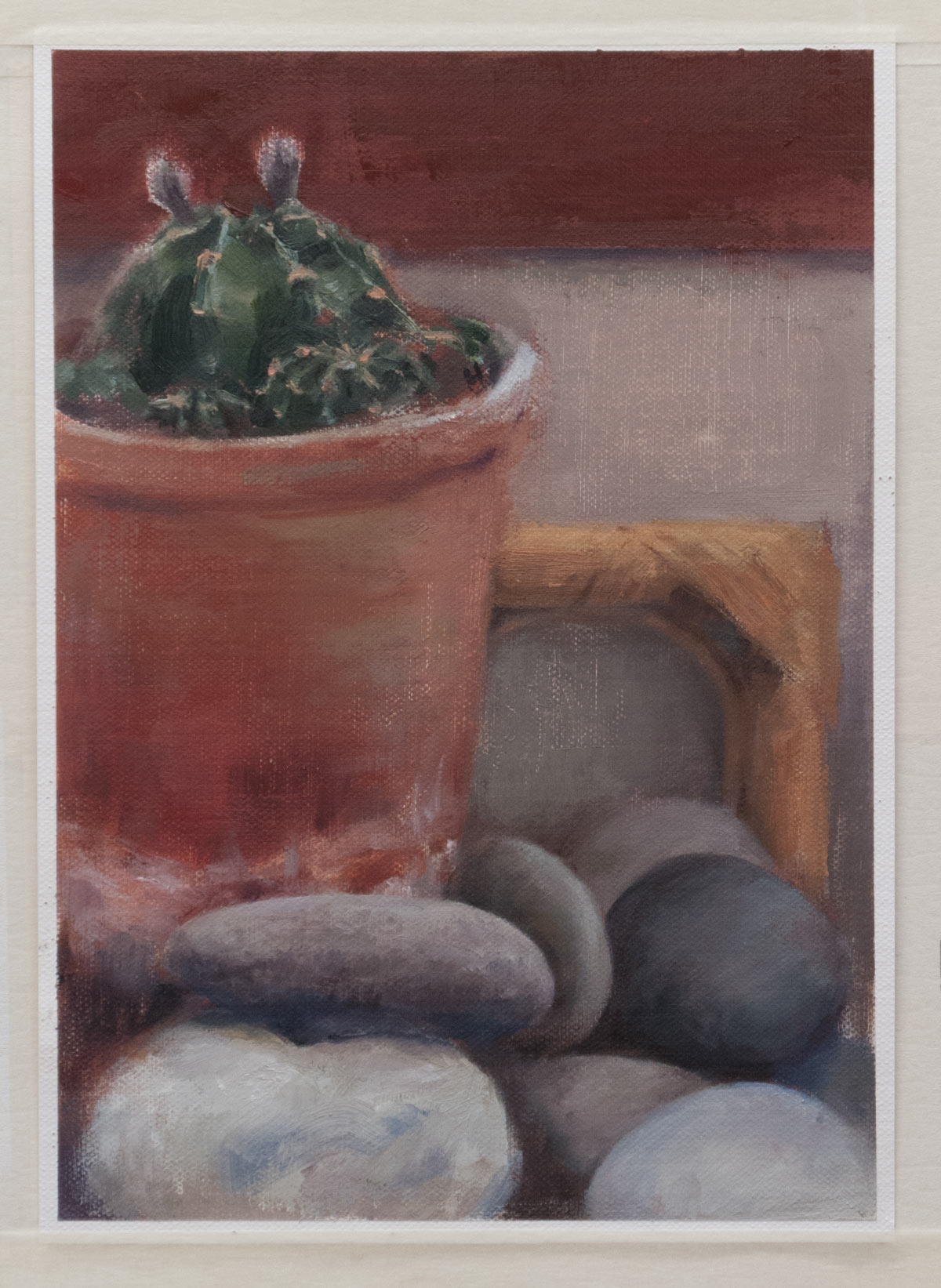

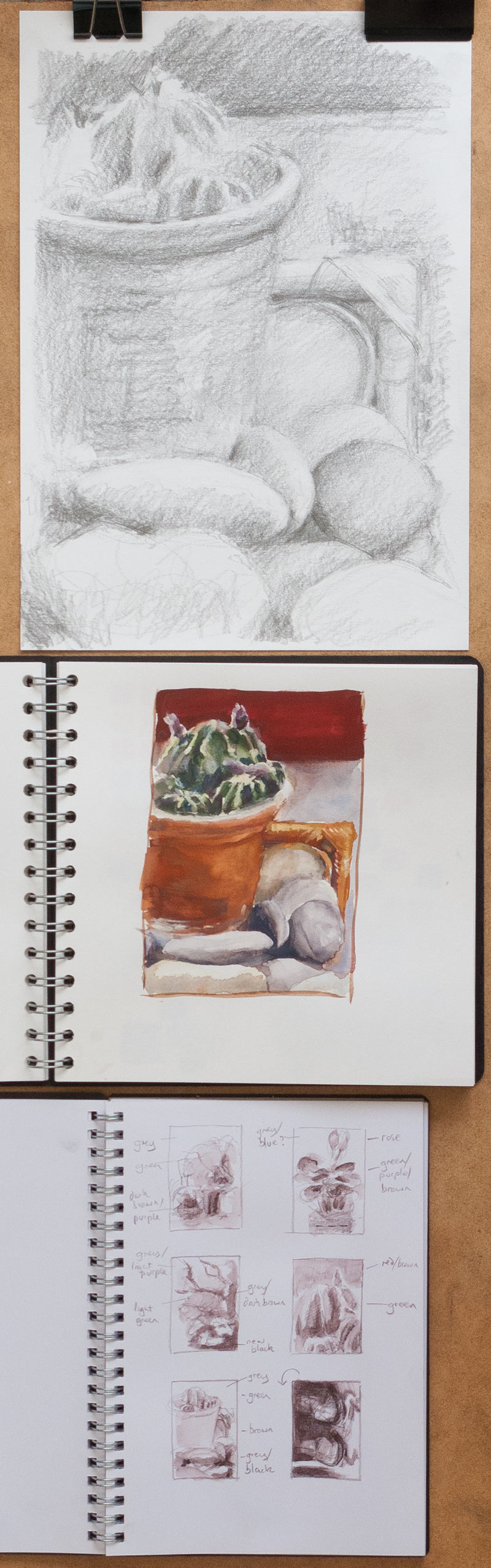

This was also an exercise in developing a method of creating a final painting. I quite like this process of starting with a pencil drawing then transferring it to the canvas, or in this case the usual gessoed paper. A scan of the original pencil copy was enlarged to the final size and printed out on normal office paper. The back of the printout was rubbed with charcoal then taped in place and the outline traced with a red ballpoint pen (red ink makes it easier to see which parts have been traced). I found it helpful to trace not only the outlines but also areas of shade. With the charcoal transfer in place I could quickly build up a tonal underpainting. After that, the experiments could begin with building up layers of paint, blending (or deliberately not blending) the tiles of adjacent colour, making many mistakes, and trying to correct them.