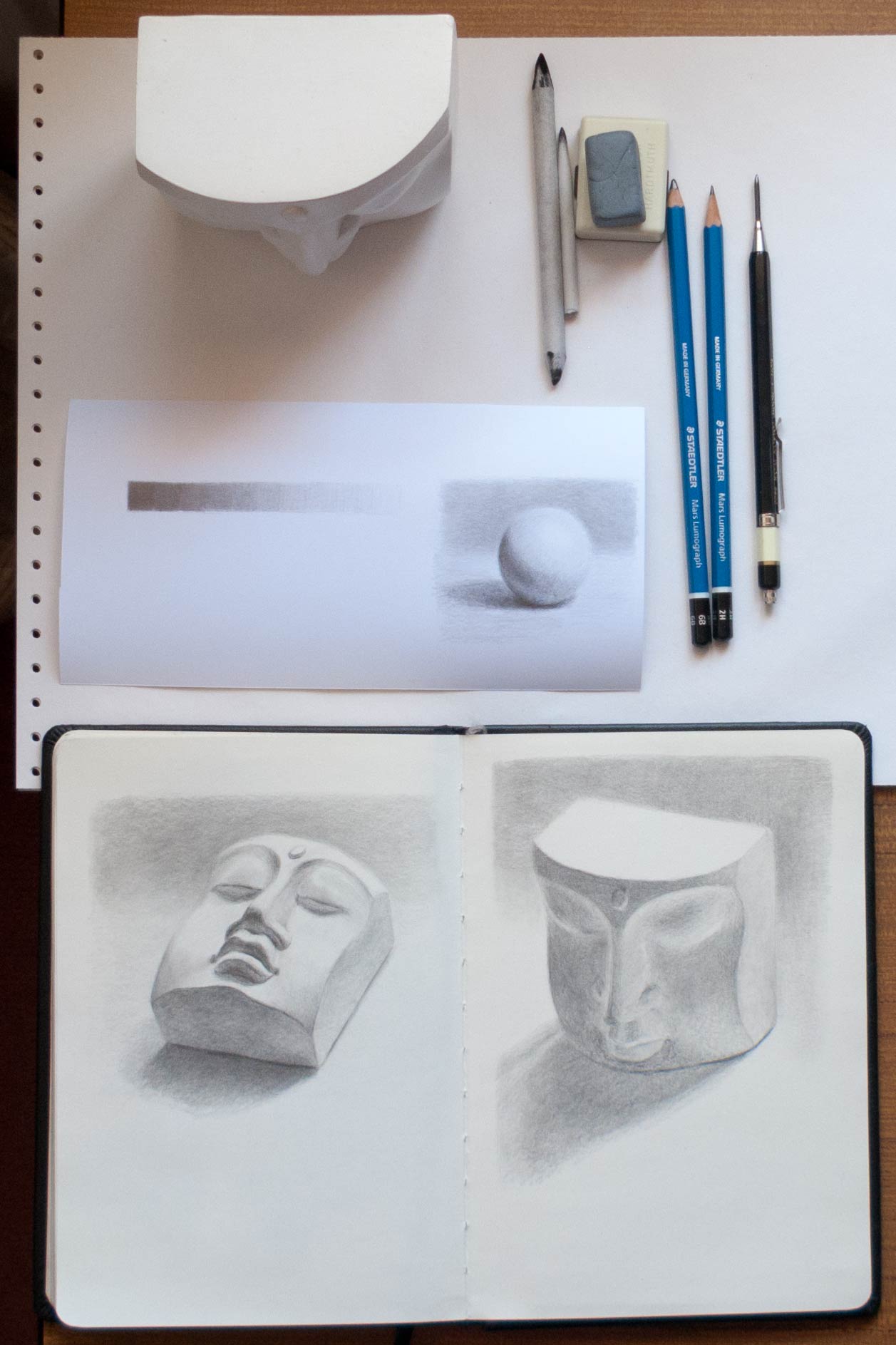

Trying out a clutch pencil and new graphite leads on Bristol board.

The advantage of using a clutch pencil is that there’s no need to whittle down a normal woodcase pencil to expose a long lead for shading on the flat side. It also stays a consistent weight and size in the hand as the lead wears down. I also like that it’s possible to get a more expressive line by using the side of the lead as well as the tip. The Staedtler range of leads seemed to get the thumbs-up in various online forums so I tried some of their Mars carbon 2B 2mm leads in a Koh-I-Noor lead holder (I prefer the weight and feel of the Koh-I-Noor compared to the Staedtler lead holders). Cult Pens had a special offer on a set of 6 Staedtler Mars Lumograph pencils ranging from 6B to 2H, so they had to be added to the basket.

The Staedtler leads are buttery smooth, especially on the toothless Bristol board. The smooth board surface also means that any graphite can be easily taken back to white with a kneaded eraser. I had to tape down the Bristol board (which is more like thin card) as it was bought as a large sheet and had been stored rolled up in a tube. In the future I think I’ll opt for pads instead of loose sheets.

Drawn from a photo found on the internet, taken by Anastasia at the State Darwin Museum in Moscow, the perspective shows off the wide looping zygomatic process (the thin bone connecting the cheek bone to the side of the skull). As the skull is a museum exhibit I couldn’t tell if this bone structure was unusual or just natural individual variation.

I didn’t use a grid this time, but I found it helpful to lightly shade in the main dark shapes right at the beginning of the lay-in to check the general proportions rather than use outlines alone. With the shading, establishing the darkest darks early on made it easier to assess how light to make the other tones. I couldn’t decide on the background: Leaving it white would hide the shape of the top of the skull. I took a mock-up into Photoshop to play around with various background options and decided that a bit of tone around the right edge would emphasise the skull shape and cheekbone. After adding this light shading I tried to blend it into a smooth tone using a paper stump but just made a smudgy mess (I’m not sure why), and in the end used a hard 2H lead to lightly scumble the graphite around.

This is an example of the limitations of working from a photo. It would have been so useful to have examined the skull as a three dimensional object rather than try and work out the structure from patches of light and dark – the back of the jaw bone was especially hard to decipher. I’ll keep my eye out for a junk shop skull.