Sketchbooks are great, I love them. They keep all your masterpieces, all your mistakes, all your experiments, all together in one place — a record of that time in a self-contained book. For better or worse, that is what you saw, and how well you could draw, at that time.

But sometimes you just want to experiment and not worry how this new page will compare to all those previous pages. When you manage to make two or three decent drawings, the next one has to be at least as good. That’s a pressure that can stop you from starting the next drawing. A pressure that can stop you from drawing altogether.

There are ways of getting around this expectation (in your own head) that you have to live up to the quality of the last drawing. One is to fill a page full of scrawls of pen testing — squiggles of run-out ink or freshly sharpened pencil. This spoils the page. The bar has been lowered. You no longer have to live up to that golden run of fine artwork. You are free to experiment and, possibly, fall flat on your face with a lemon of a drawing.

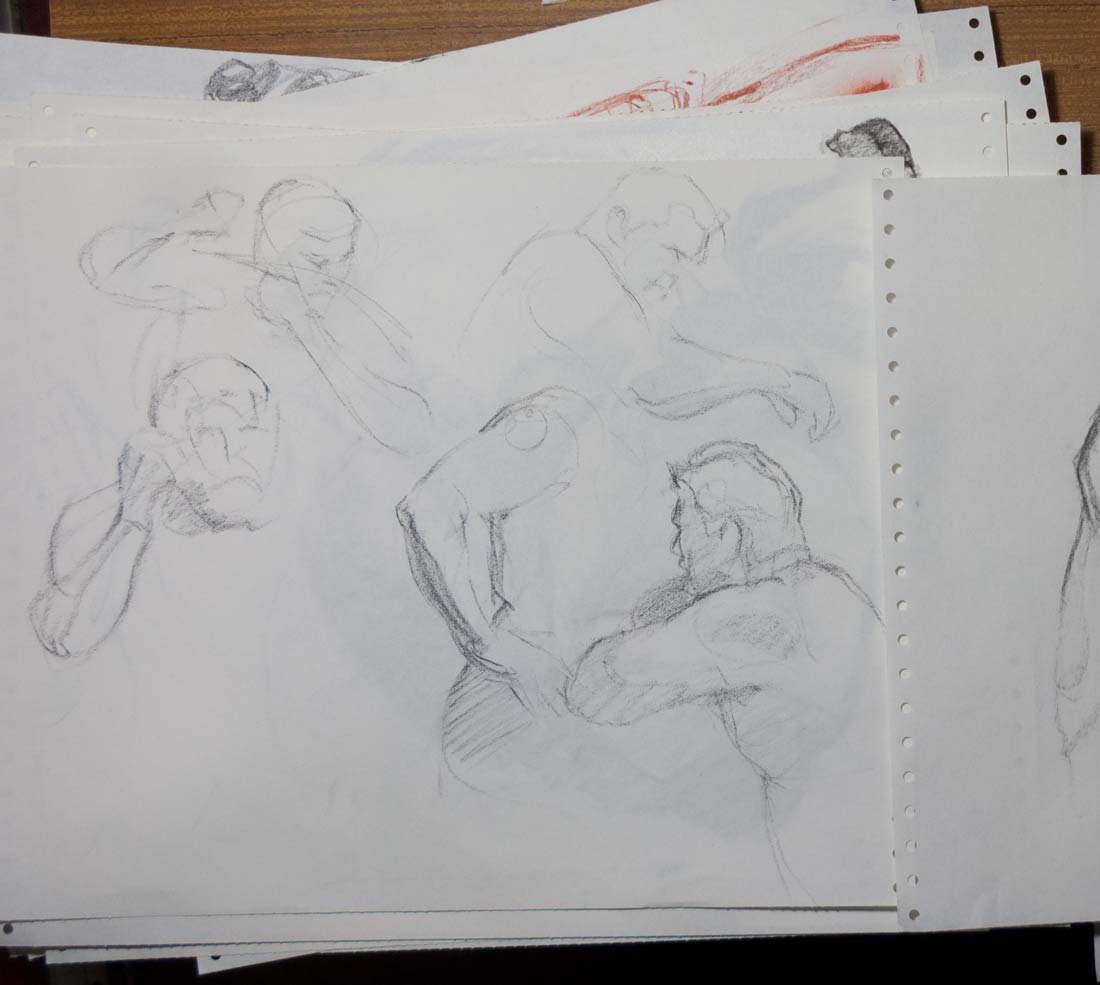

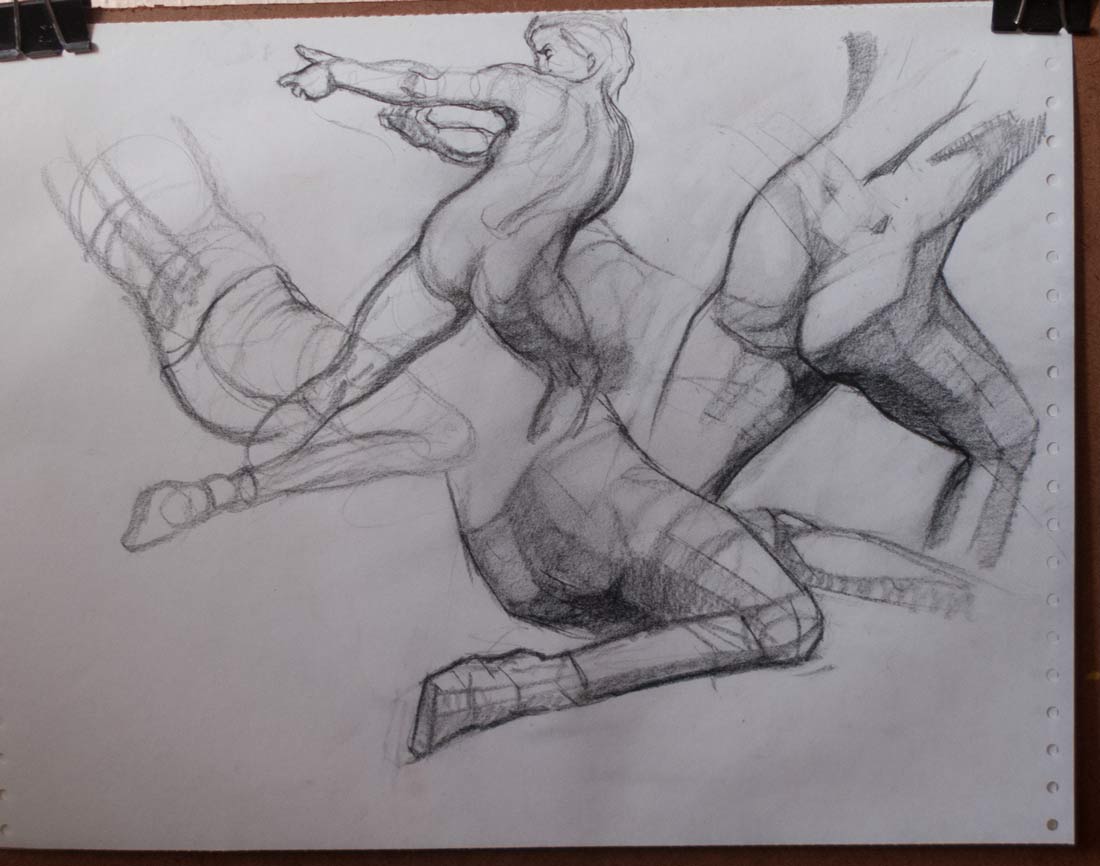

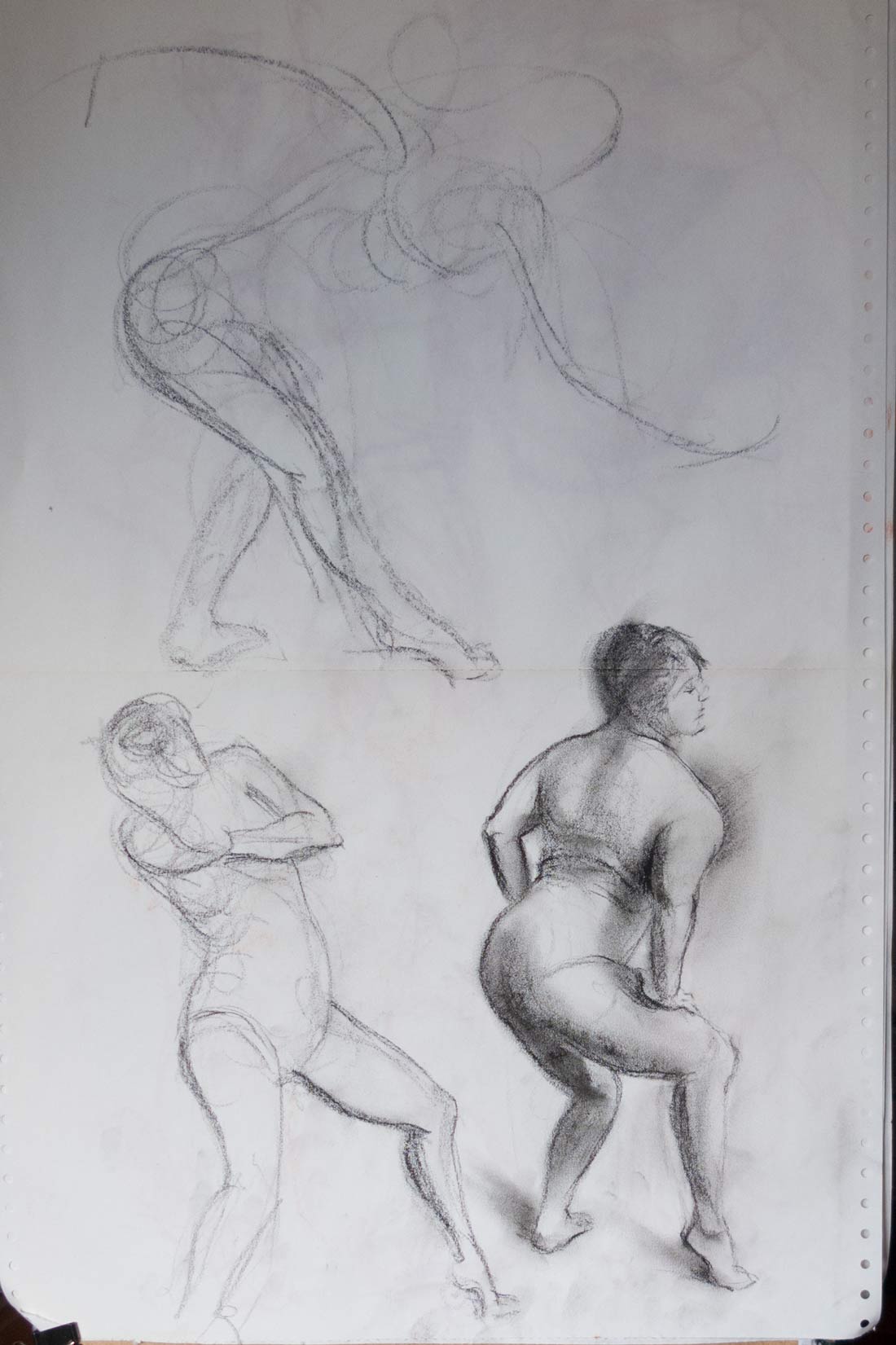

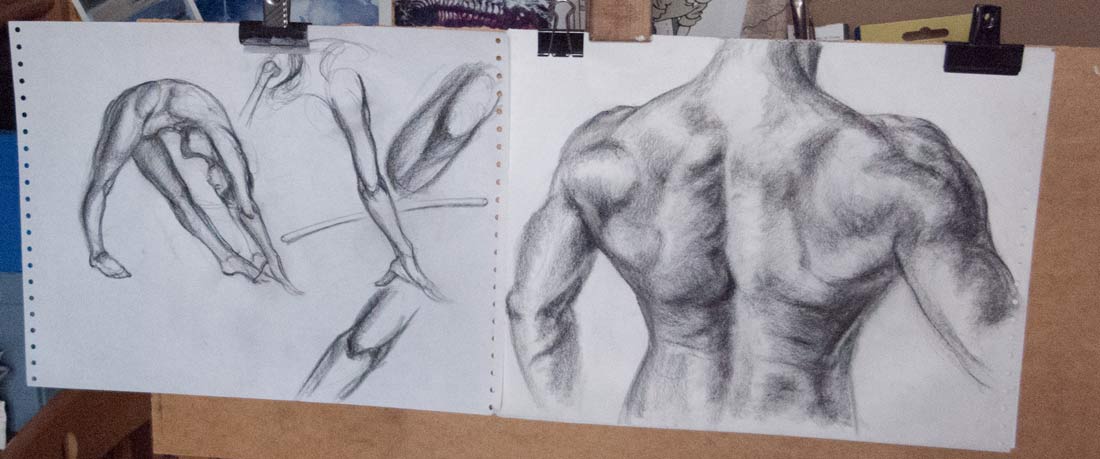

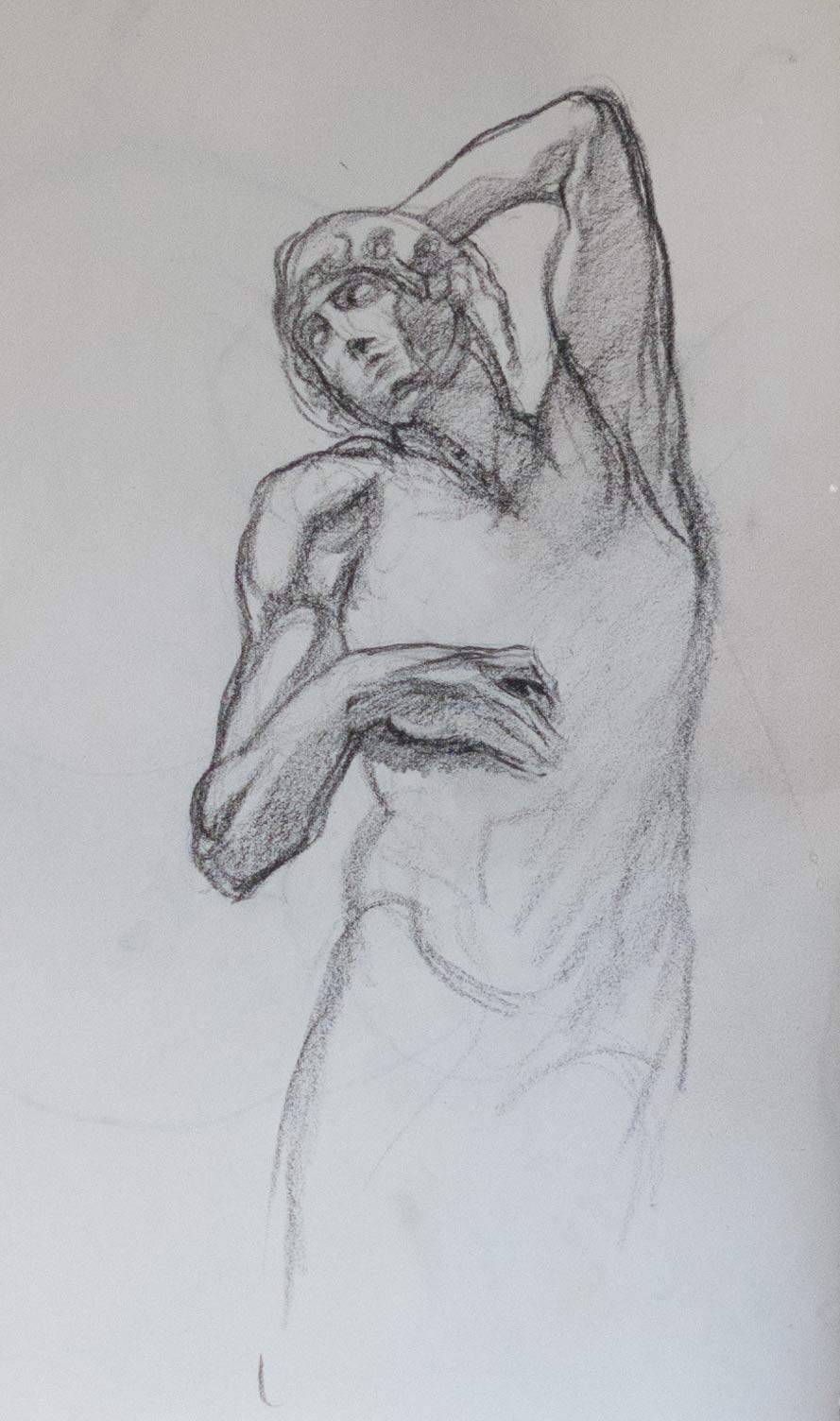

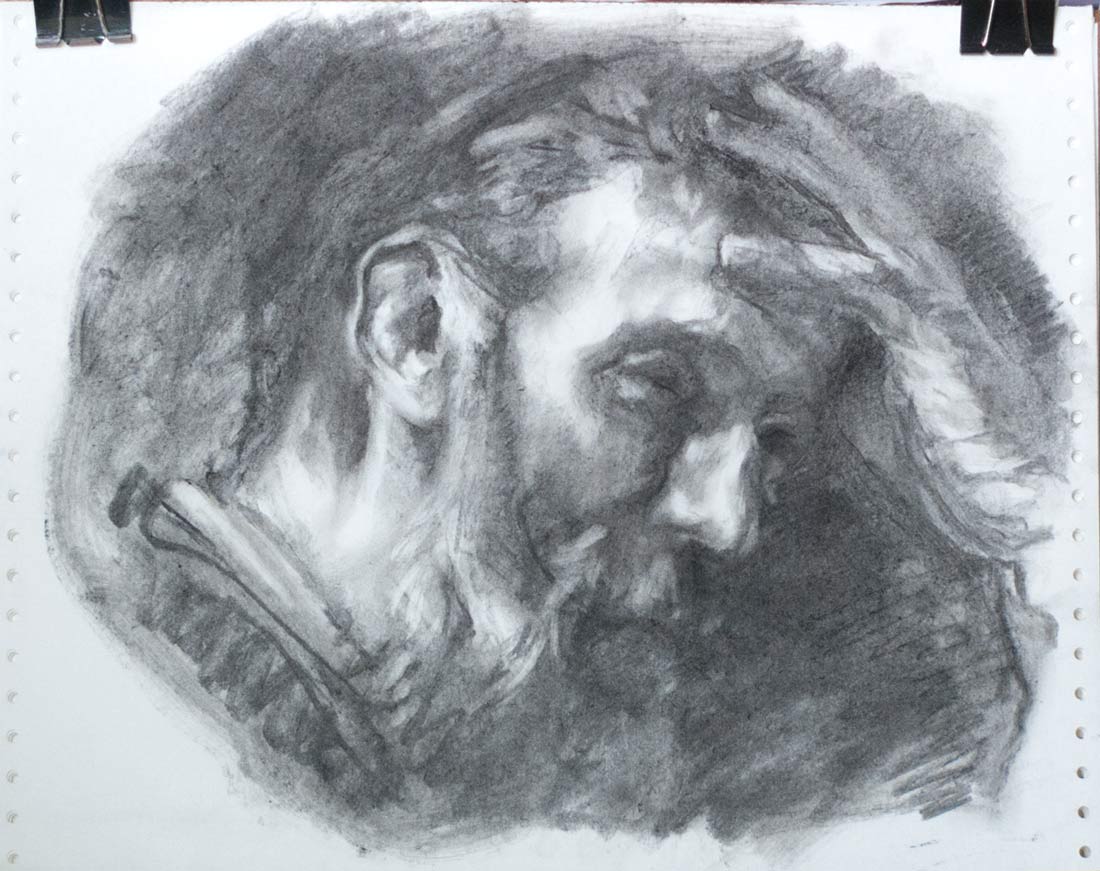

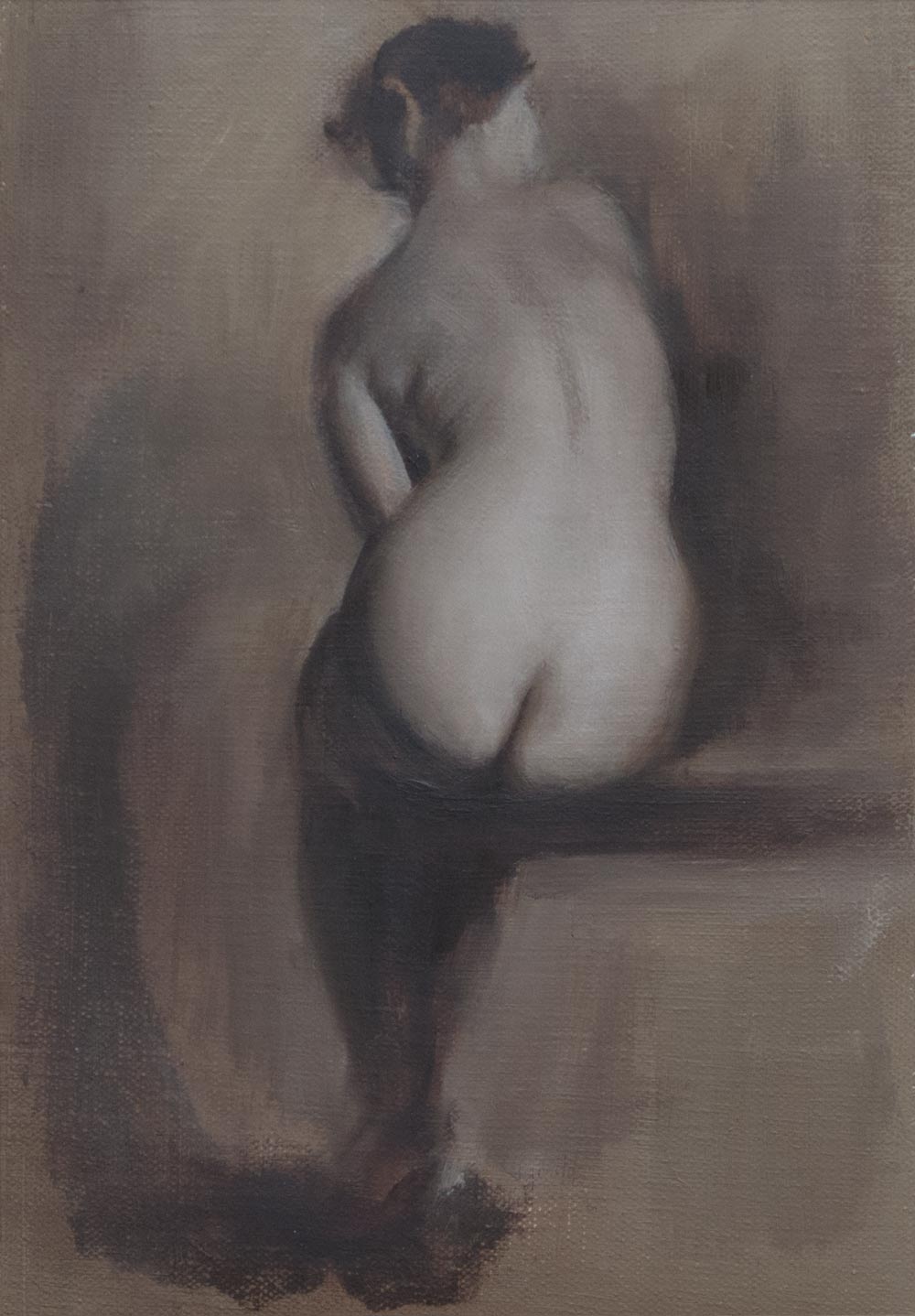

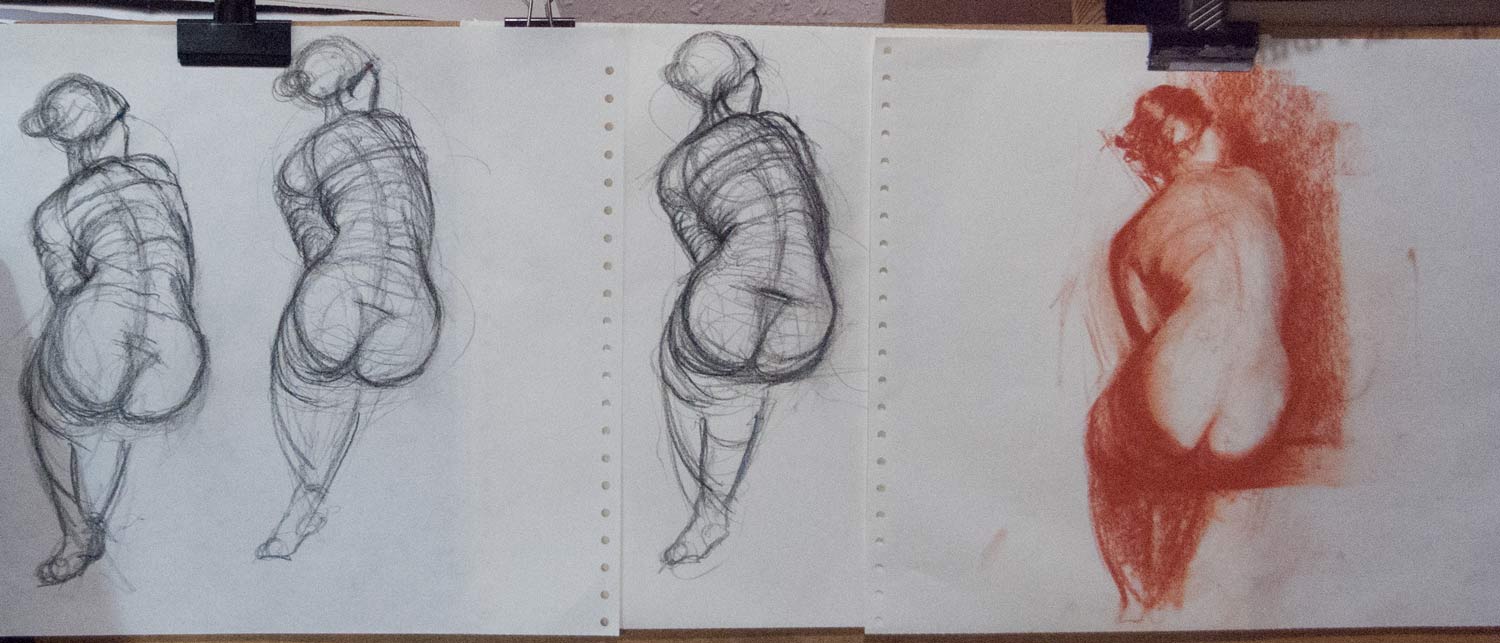

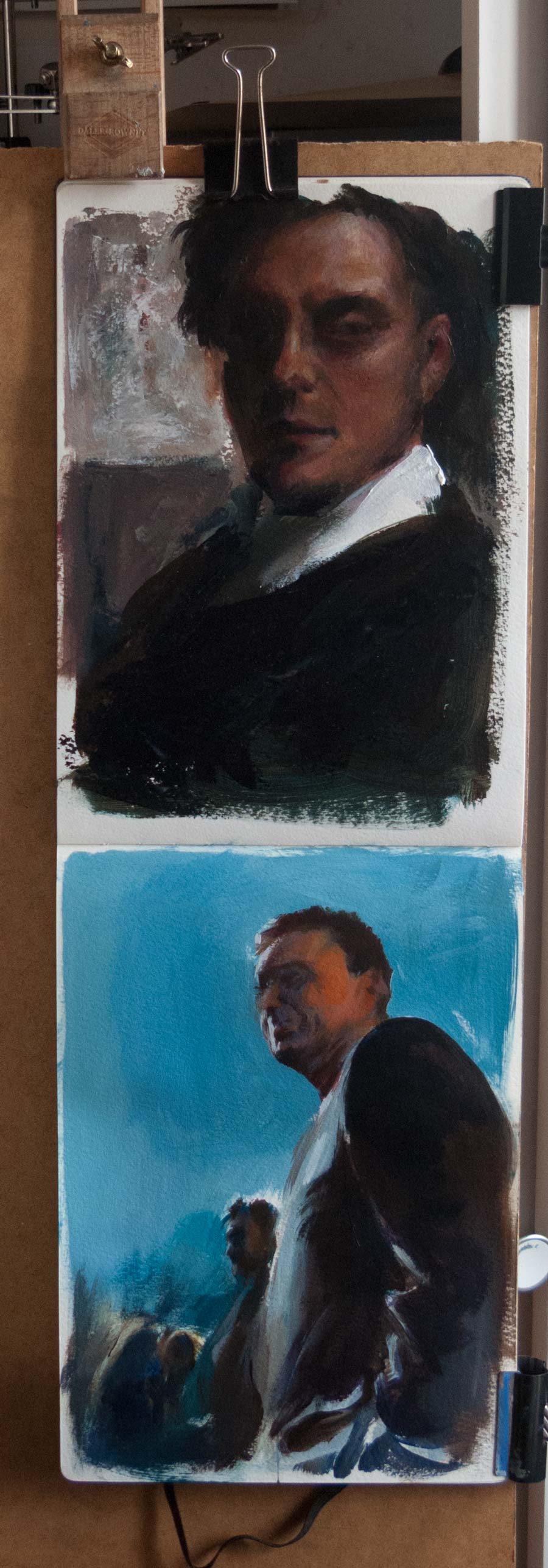

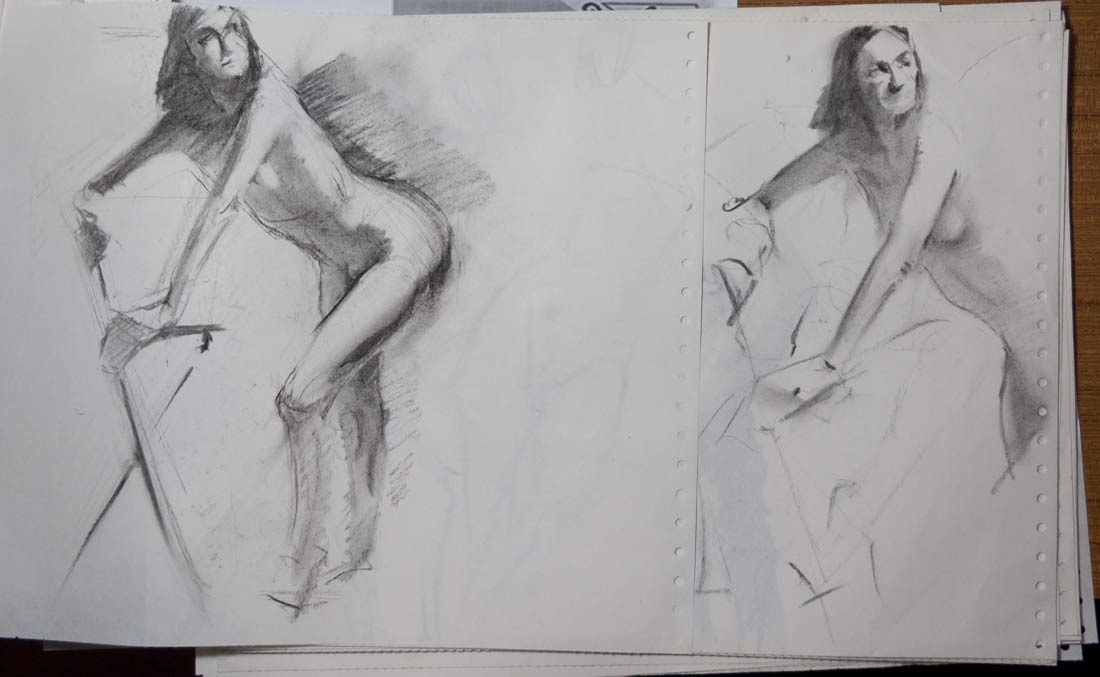

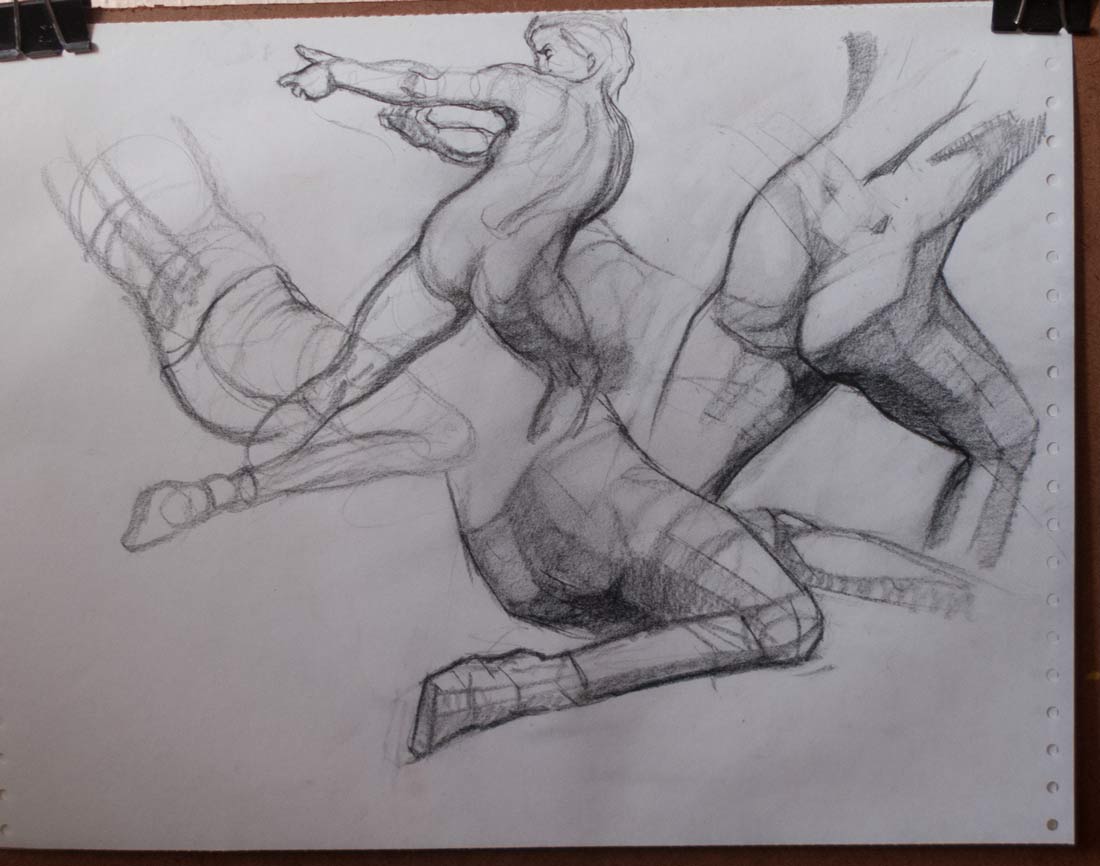

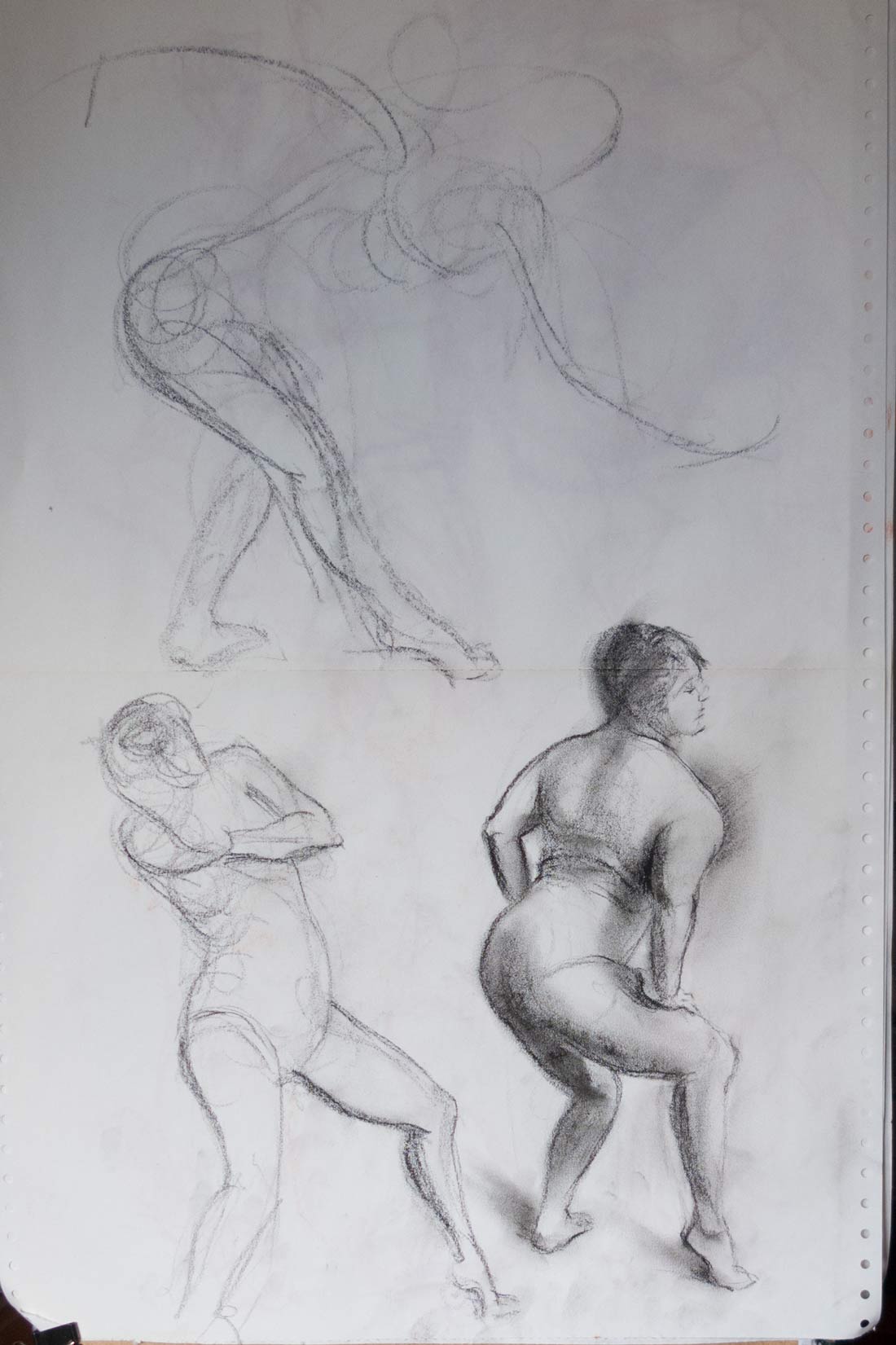

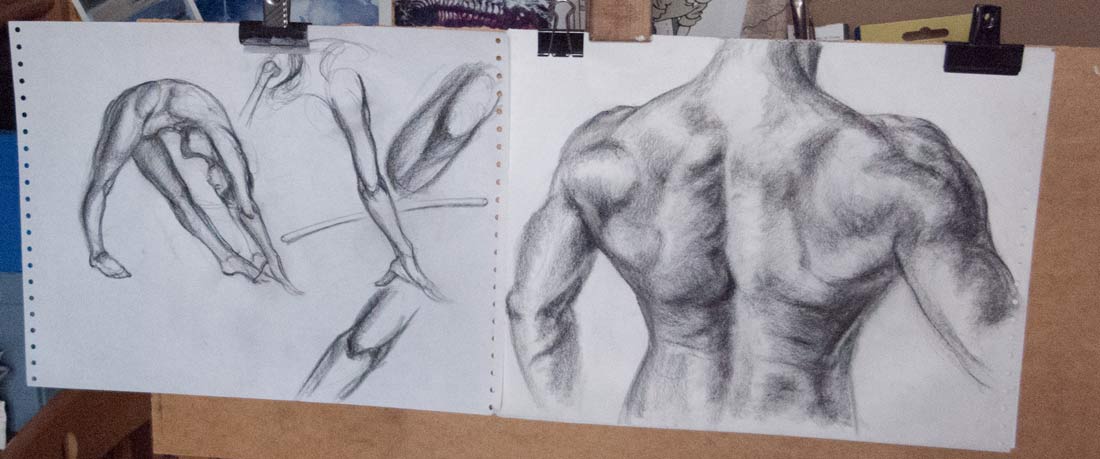

Sometimes you don’t even want to lower the bar. Sometimes you just need to scrawl, scratch and belly-flop your way through a whole bunch of drawings that will never be seen. This is valuable. It is important to practise, to get it wrong, again and again. The results will be a mess, arms will be drawn too long, heads will look like deflated footballs, hands will be stunted stubs, but it doesn’t matter. You have to make mistakes, takes risks, try things out, and do it all away from the public gaze. If every piece is for show then there’s a tendency to play safe and only use methods you’ve used before.

There are parallels to sports training or mastering a musical instrument — endless repetition, making the awkward and difficult rewire into muscle memory. And most importantly (otherwise you’ll never do it), you have to love the process of training.

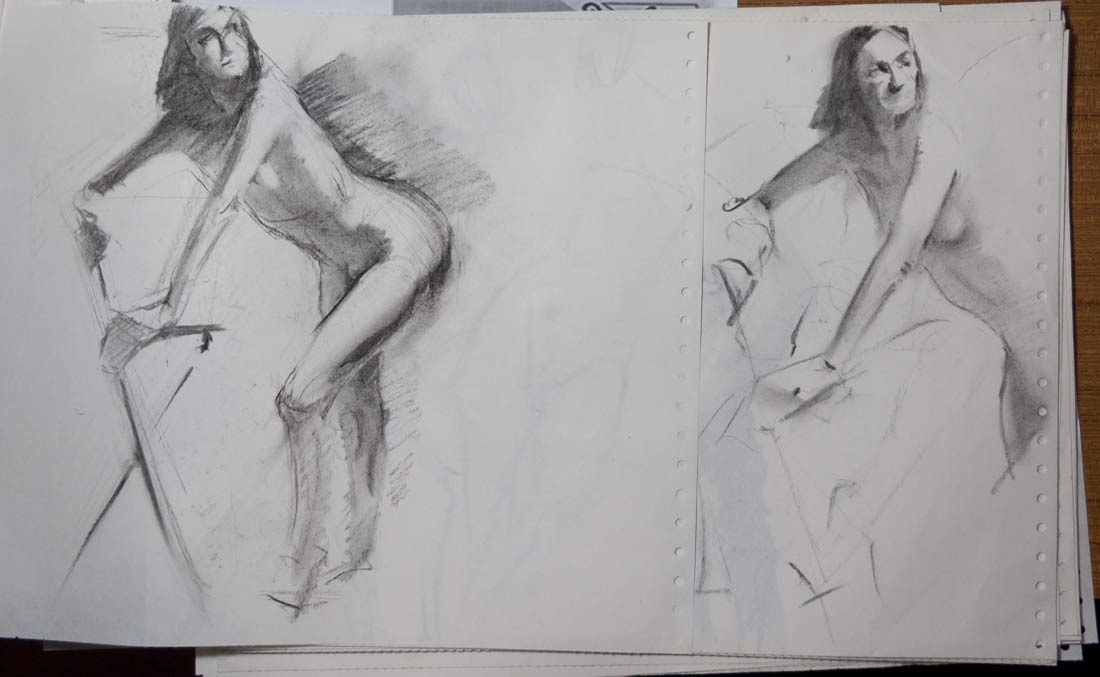

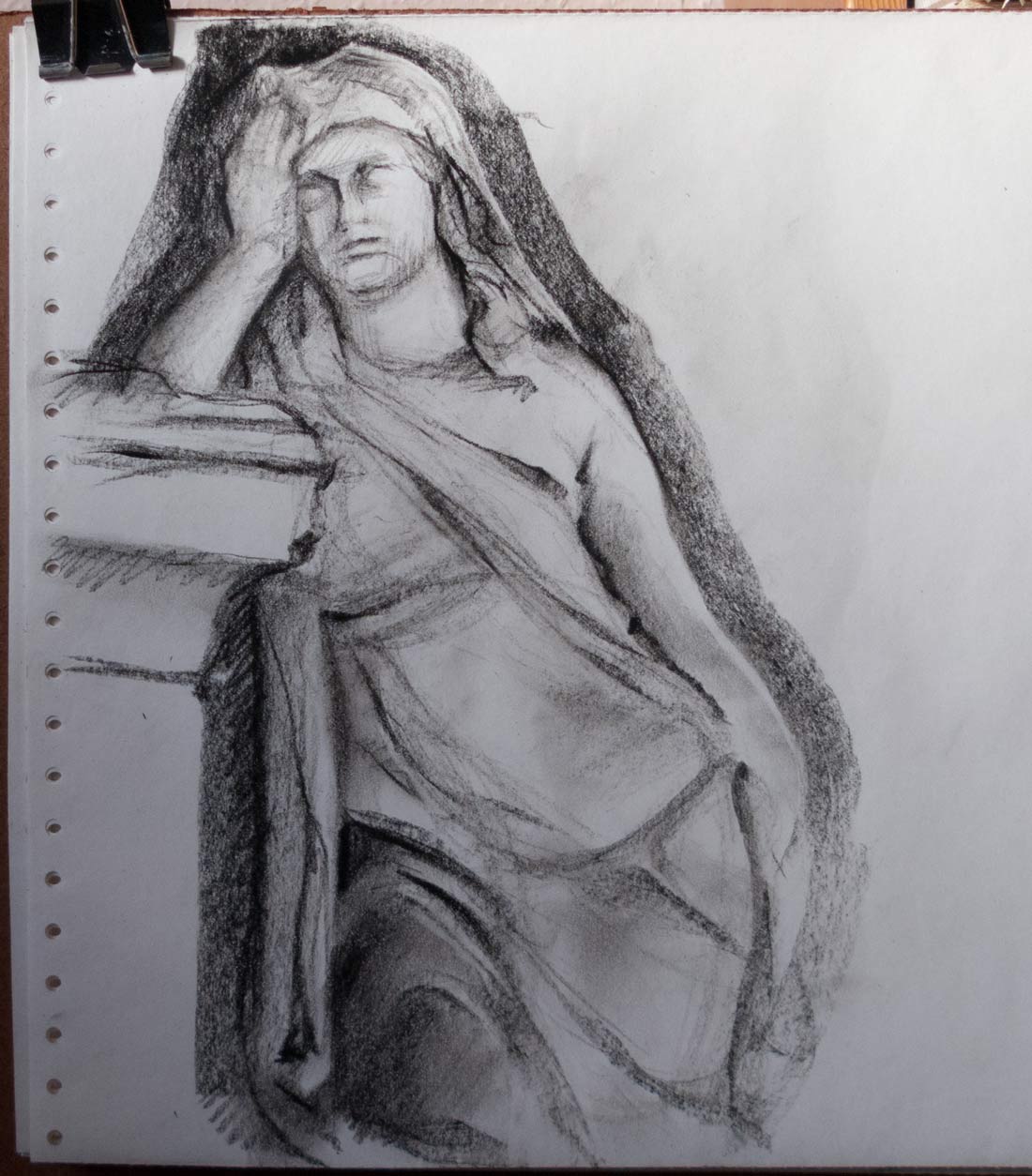

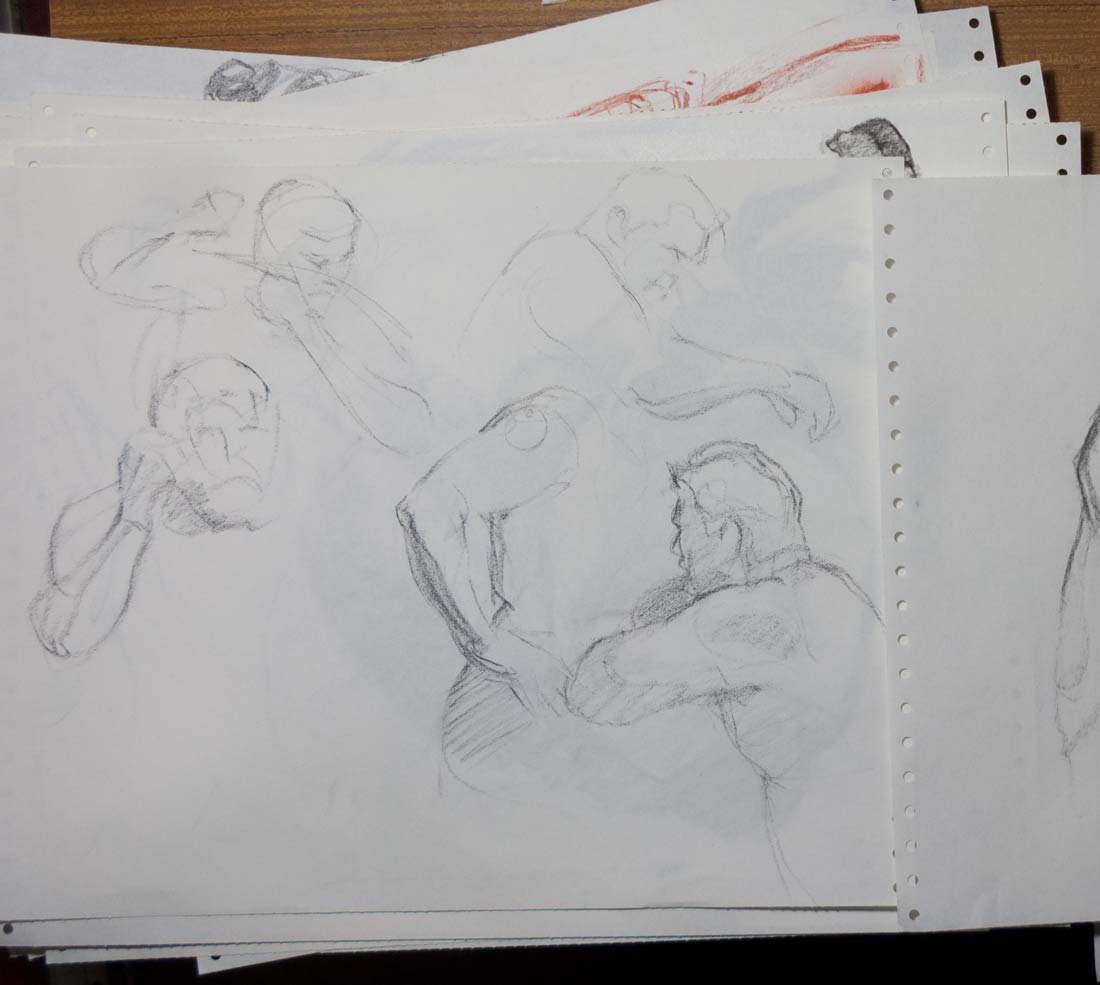

Some time back I found a box of printer paper in the back of the garage. It was that perforated printer paper with holes in the side — one long, box-deep piece of seemingly endless paper. It was smooth on one side and rough on the reverse, much like shop-bought artist’s newsprint.

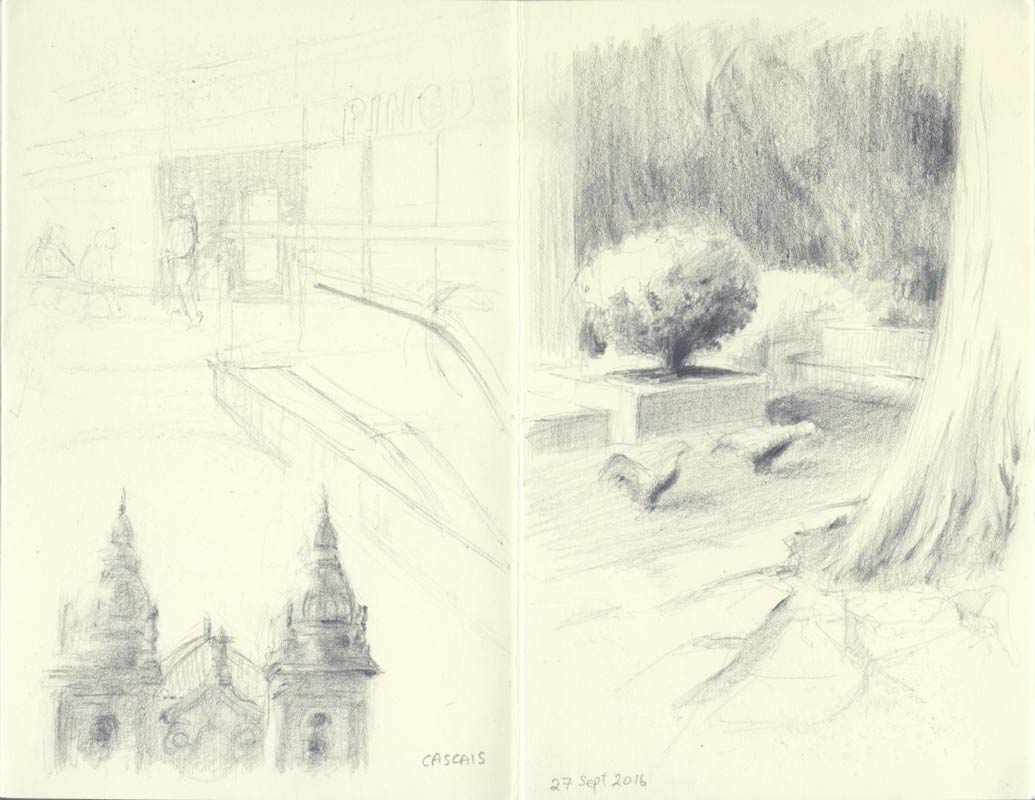

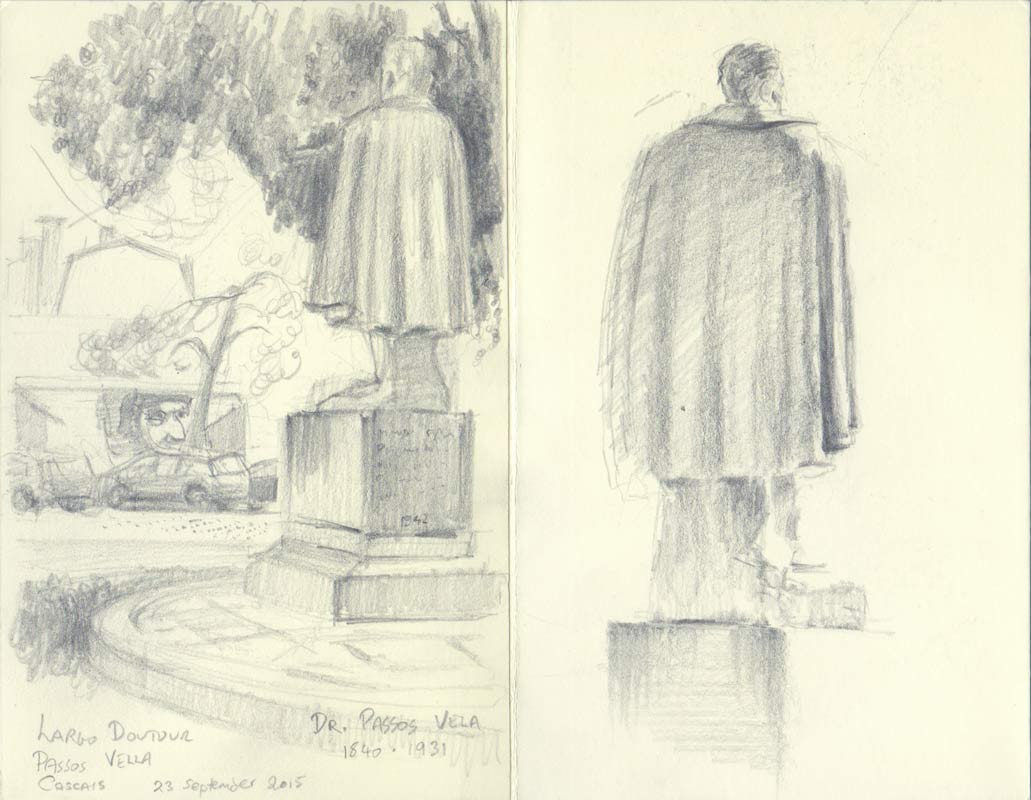

Lately, it has replaced the sketchbook. That’s not quite true: I still have a number of sketchbooks on the go — one stuffed in a rucksack for those moments of sketching on a park bench or waiting in a car park. Another, with thicker paper, has paint thrown at it. Yet another contains watercolours or gouache or ink. This computer paper isn’t a replacement, it’s a place to experiment.

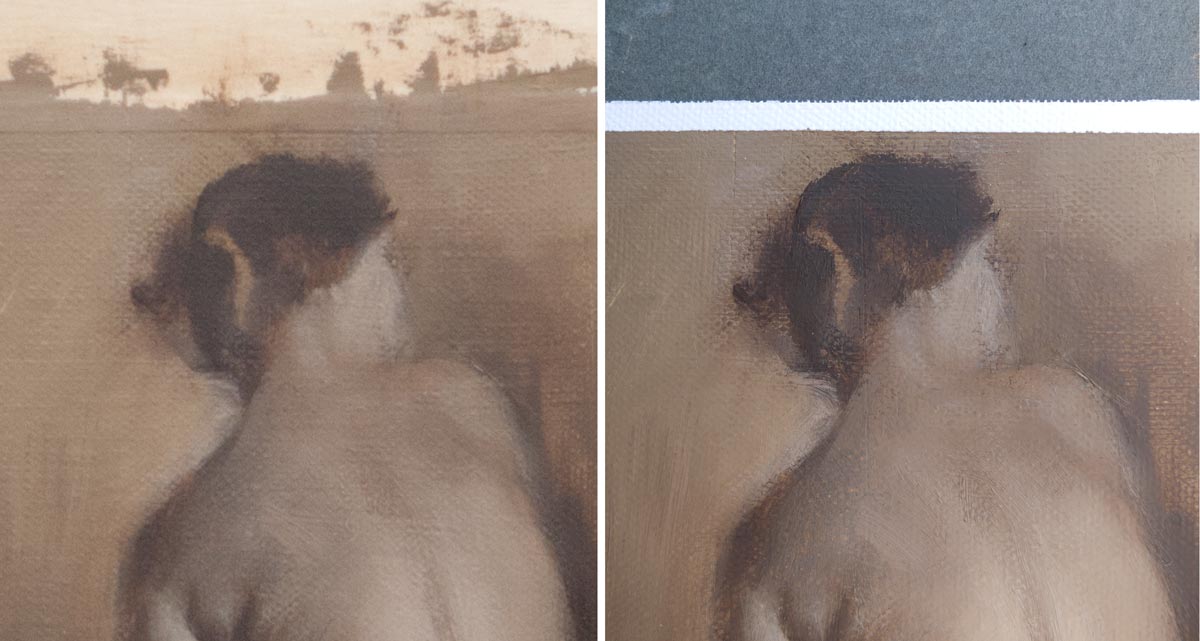

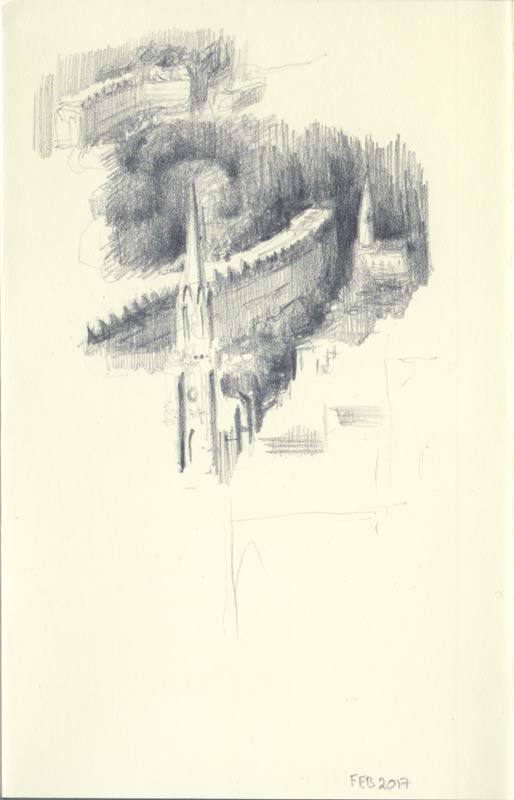

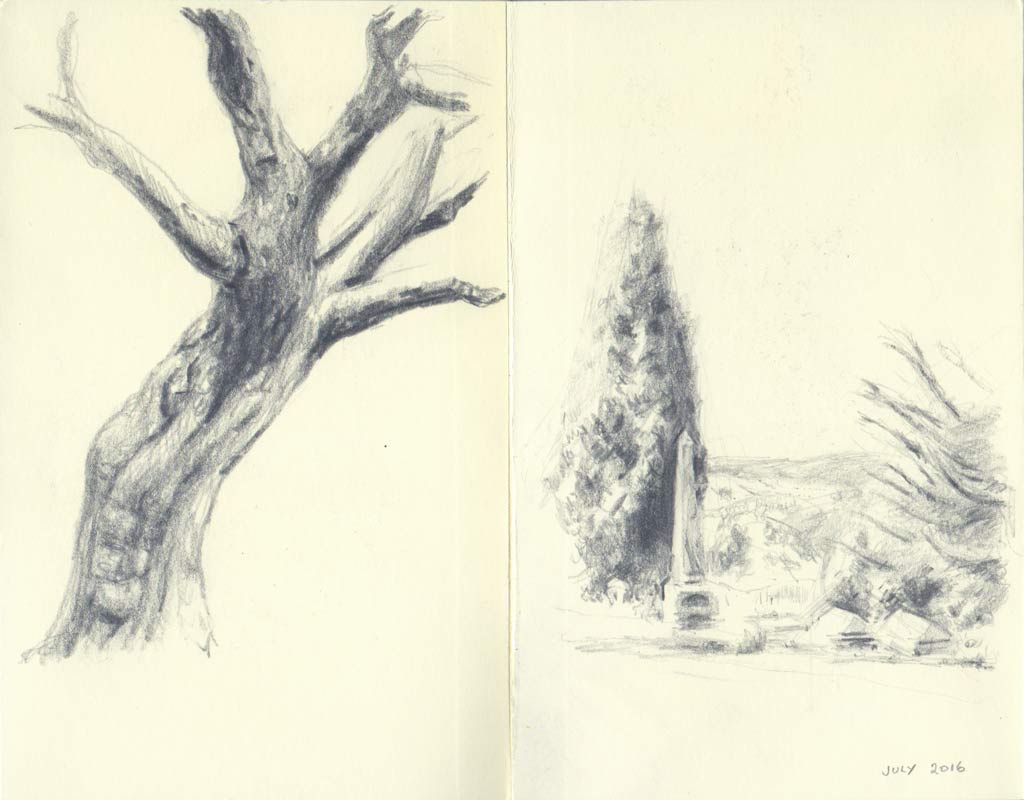

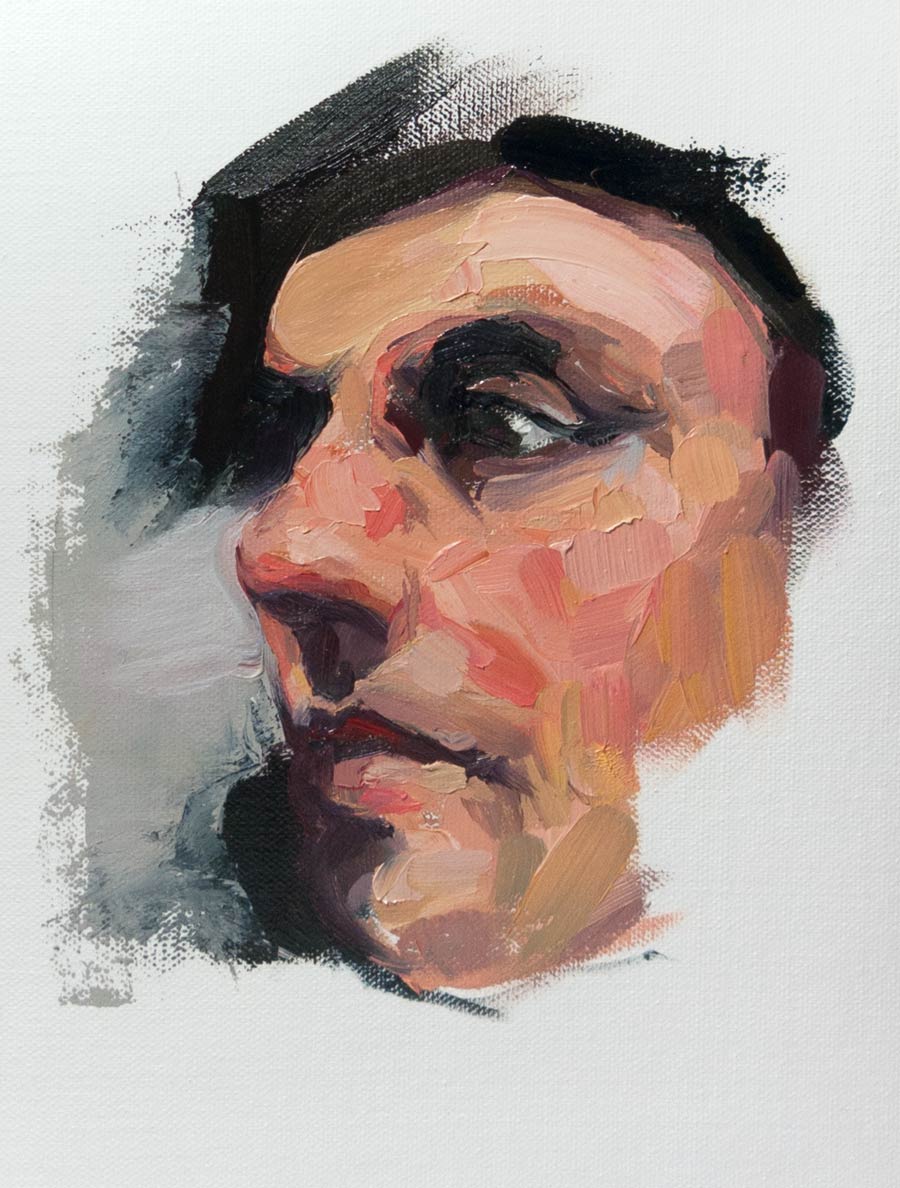

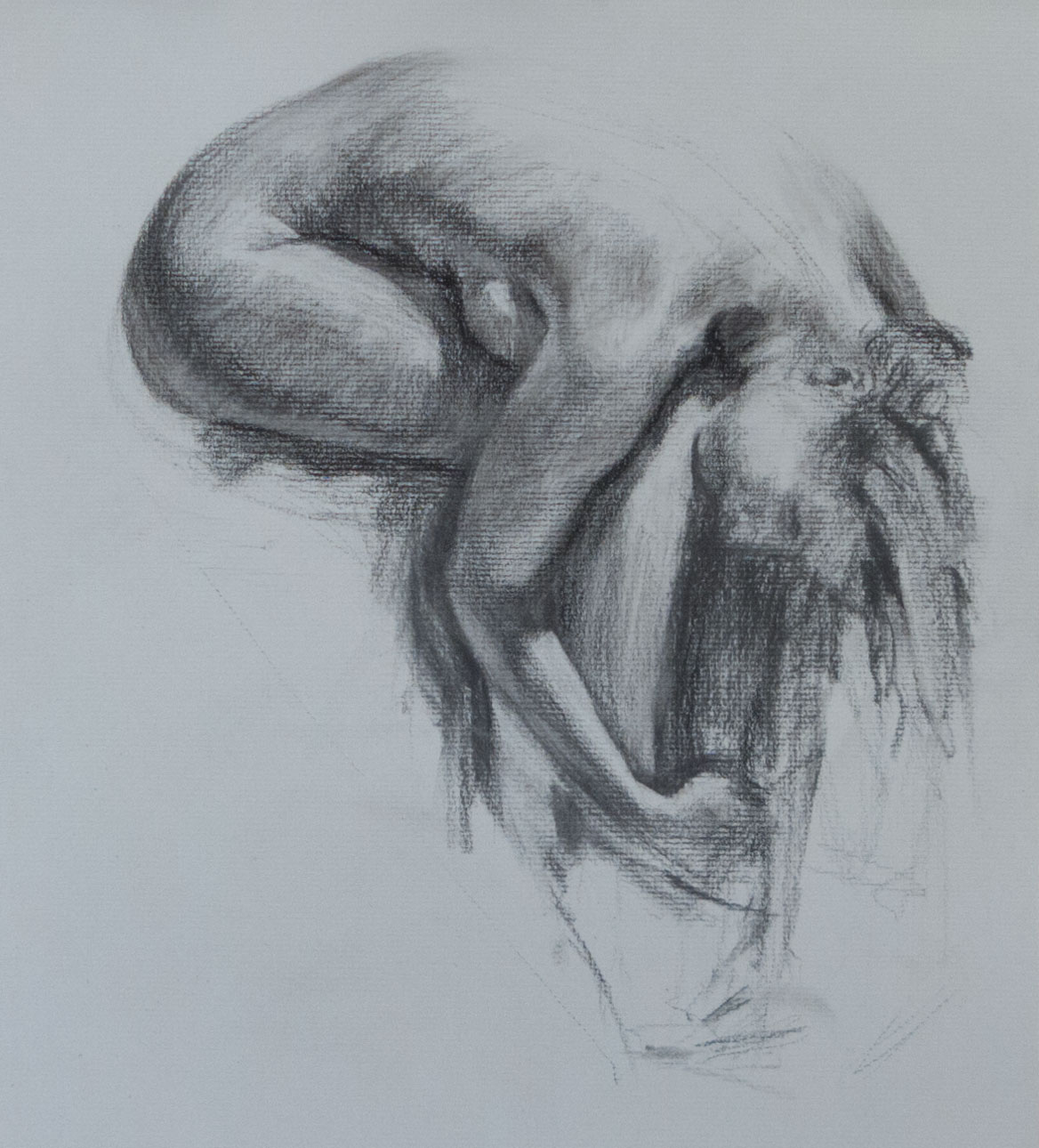

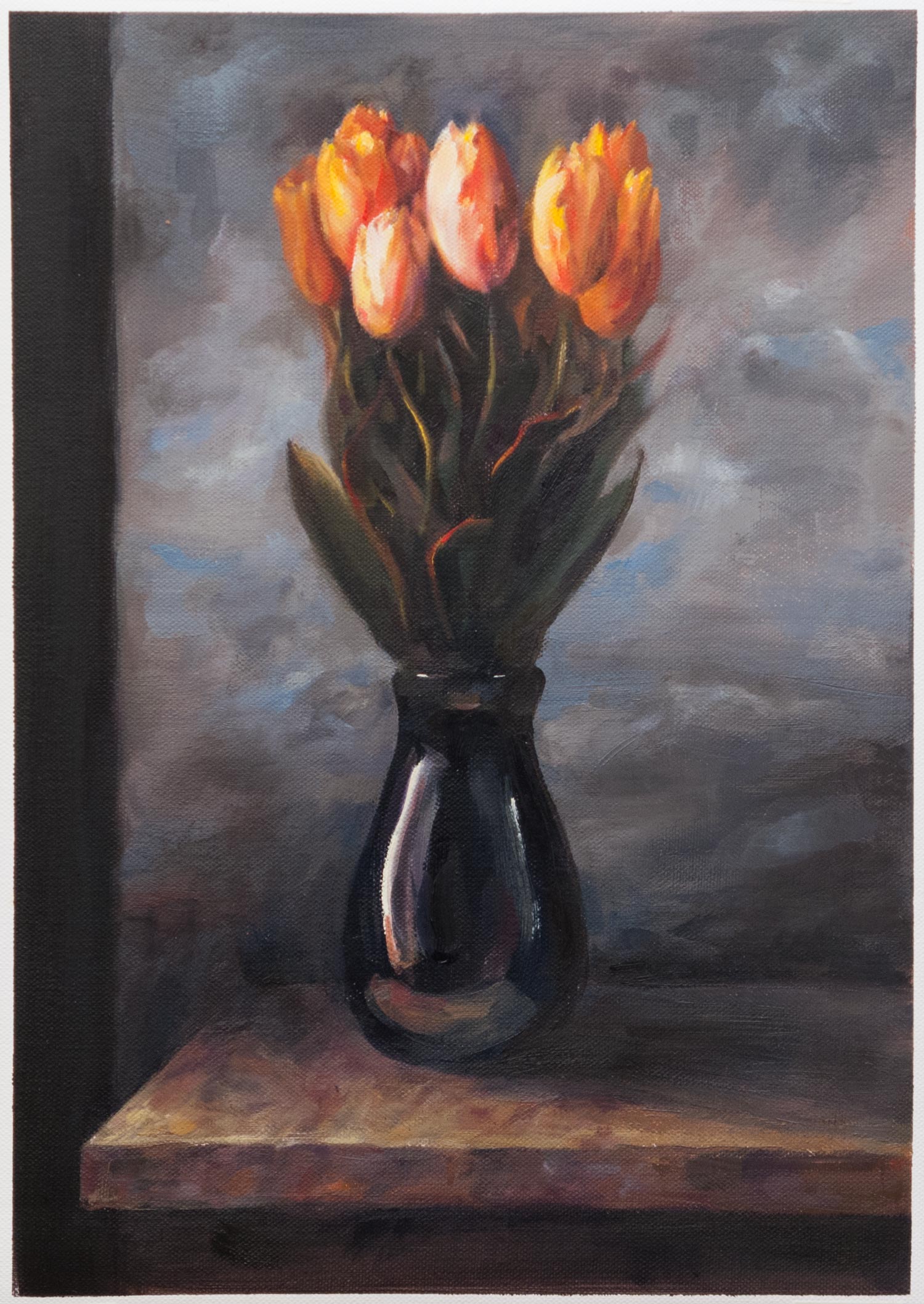

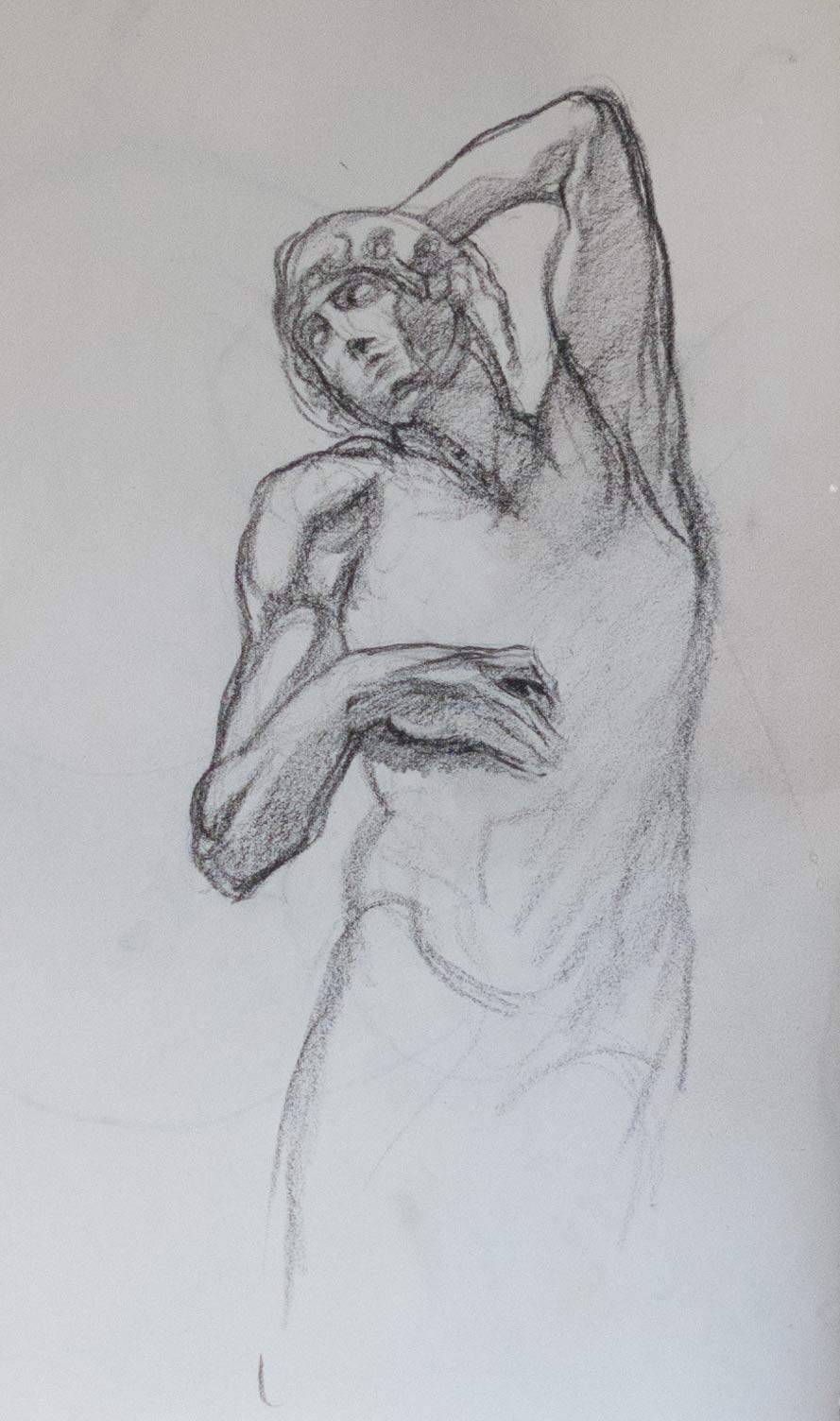

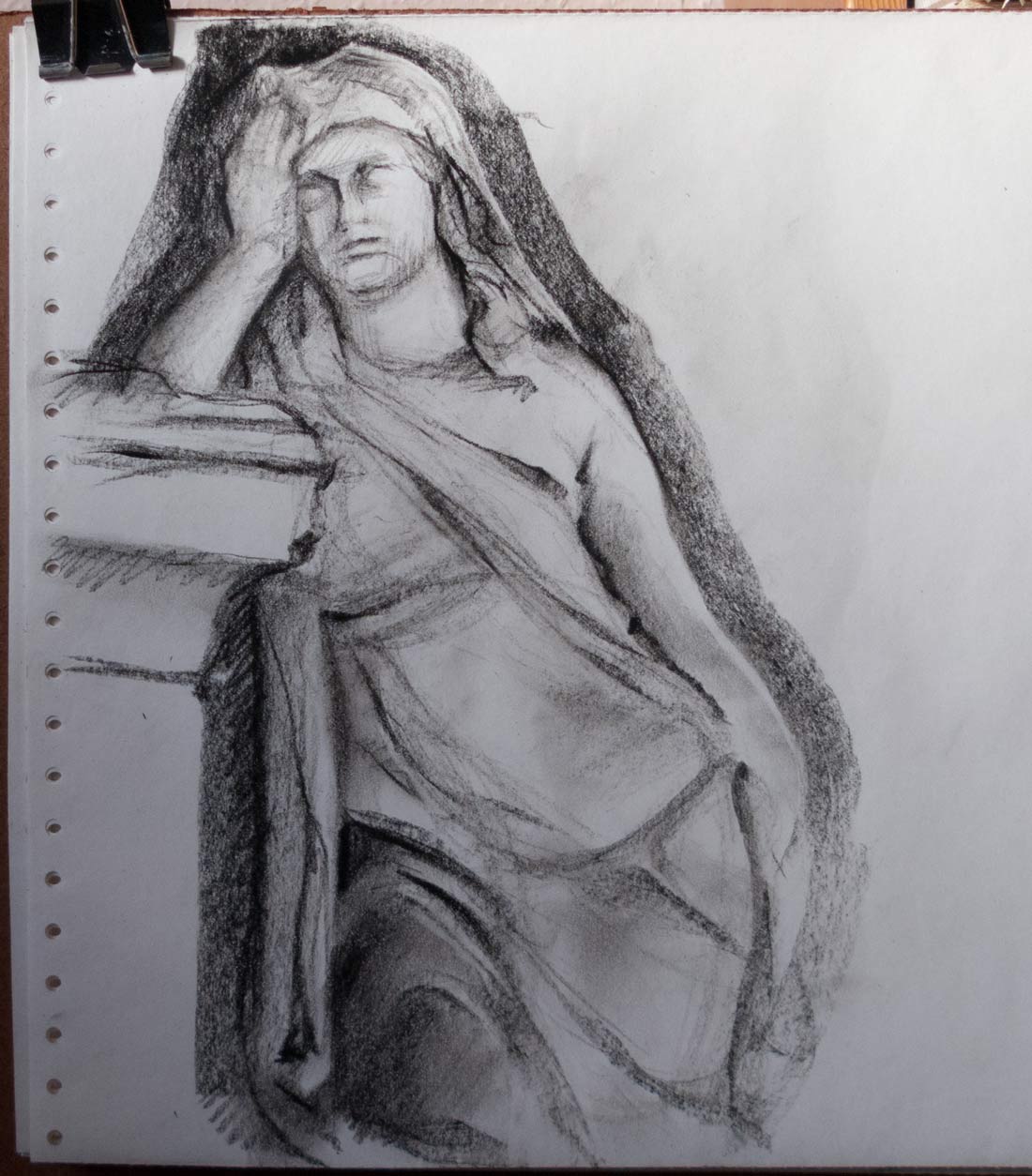

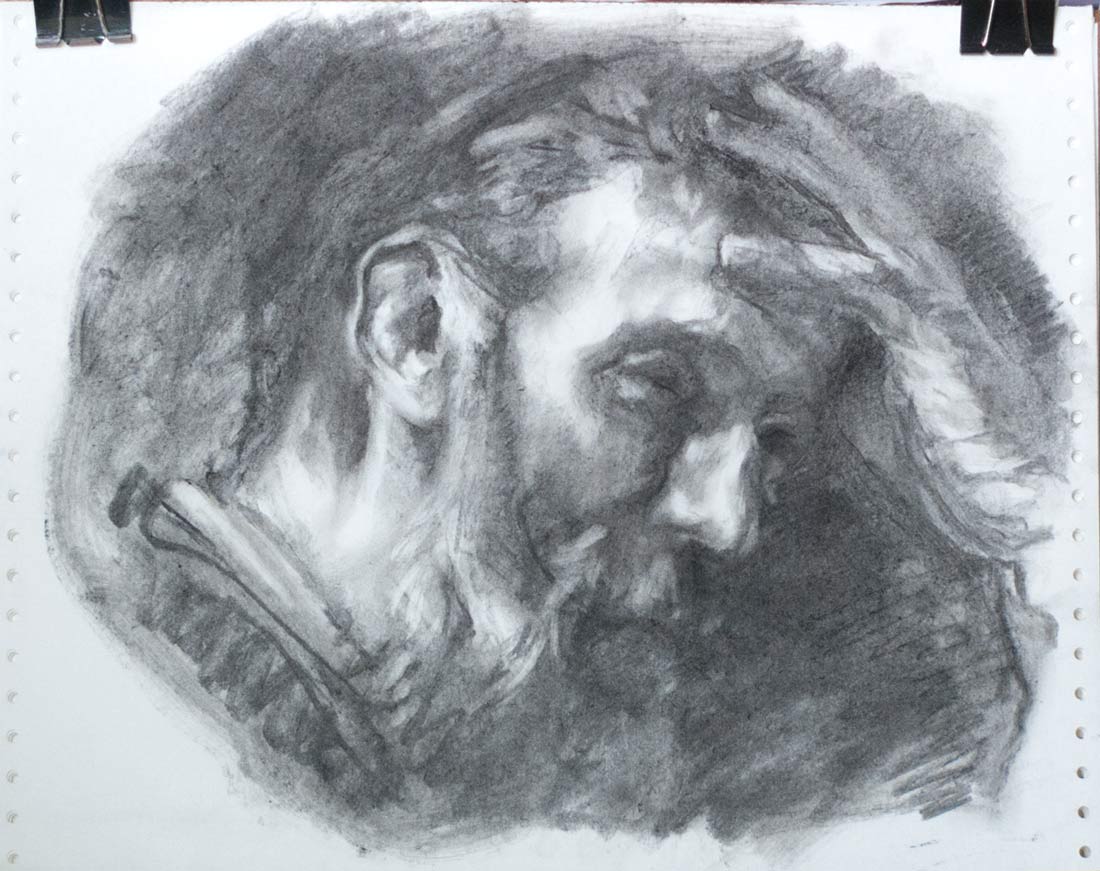

Of course, the ones shown here are a selected batch — many of the sheets are filled with unremarkable 1 minute gesture drawings. quick sketches, warm-ups, or overworked dark-grey multi-lined smudges — a necessary graveyard of lemons. They all end up being stuffed into a corner of a cupboard, so I take a snapshot of some of the ones that have something interesting about them, or sometimes I’ll take a photo just to record the way I draw at the moment. Hopefully, I’ll be able to look back in years to come and see an improvement.

When this box runs out, I’ll go online and order a ridiculous amount of cheap paper, probably not intended for artists but sold to wrap ornaments for a house move or to wrap fish & chips.

Someone once said, to become good at drawing you need to encircle the world with newsprint. I haven’t encircled the world, but I’m approaching the Ilfracombe & Barnstaple section.