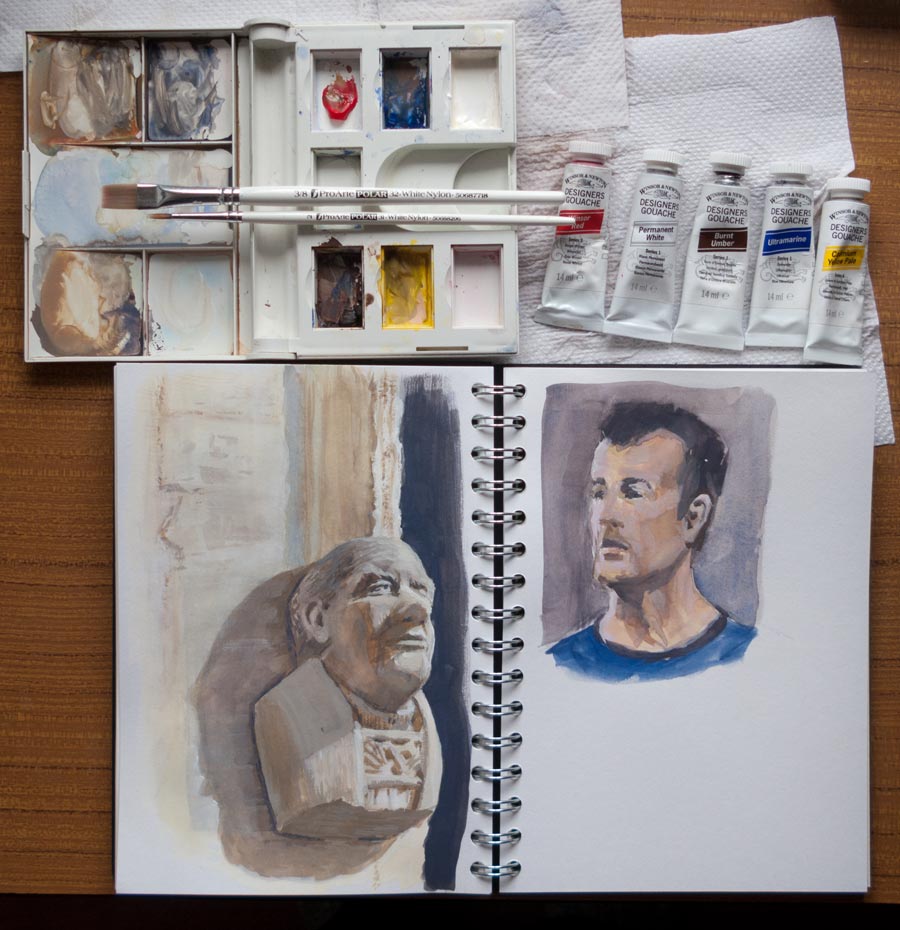

Copied from a photo and from life using oils on paper, this painting took a beating as I tried to get it in to shape.

The first problem was finding the right mix of paints to match the intense, saturated mid-green colour of the transmitted light passing through the mint leaves (yes, they’re mint leaves). I had ultramarine blue and azo yellow but really needed something like phthalo blue to get that high chroma acid green which could be adjusted with yellow and titanium white.

I ended up buying a tube of Winsor Blue which had the colour labelled as PB15:3. Only later did I realise that I’d bought Winsor Blue Red Shade when I really needed Green Shade (PB15). Also, the tube was regular oil paint, not the water-miscible oil I was using. I was hoping (after reading online forums) that I could clean up the brushes with just soap and water, after all it is just oil. It does clean up but needs a lot more working in to the bristles of a lot more detergent than is needed for the Holbein Duo Aqua oils, and phthalo blue being an intense staining colour doesn’t help.

Anyway, all that palaver resulted in the rather insipid green on the right-hand leaves.

The backdrop was a black shirt hung up behind the vase which was sitting on some white kitchen roll. (I thought a white surface would be an improvement on the imitation wood formica table top — am I ruining the mood?)

I managed to mix up the background black a little too well, and the first draft looked dead and flat. Closer inspection of the flowers showed they had more depth and variety of values than I had initially painted, so I decided to try glazing on some darker values to create more contrast.

Instead of burnt umber I used a mix of more translucent paints for the glaze, hoping I could build up tones while letting the colours beneath shine through. In my haste the glaze mixed in with the titanium white of the table top which I hadn’t allowed to dry. The resultant murky mess was nothing like the subtle glazes found in the paintings of the old masters, instead it looked as if I’d spilt something.

I used more kitchen towel to scrub off the ‘glaze’ and tried a few more times, with similar results.

Eventually I got to that point where I knew the painting was lost. So I patched up the table top and shadows as best I could and drew a line under the whole exercise. The murky grey brown lighting doesn’t complement the inaccurate greens. The lighting is flat, the arrangement of flowers too literal (what’s going on above the carnations?). Composition, colour, value, lighting — there’s a lot to learn. At least now I know some of the ways not to do it.